How Do Kids Learn to Read?

AUGUST 15, 2023

Why do so many students struggle to read? The most recent NAEP results show that just 33% of 4th graders and 31% of 8th graders are proficient in grade-level reading. Aligning reading instruction with the body of research known as the science of reading can improve the odds of student success. Thinking Maps can support research-based reading instruction with practical, brain-based tools for word recognition and language comprehension.

What Makes Reading So Hard?

Reading is one of the most cognitively complex tasks that most of us do on a regular basis. While many of us eventually reach a level of fluency that makes reading feel easy, there is a lot going on inside the brain when we read.

- Visual Processing: When you look at a text, the light reflecting off the page enters your eyes and is converted into electrical signals, which are sent to the primary visual cortex at the back of your brain (in the occipital lobe). This is where basic visual processing begins. (This will be replaced by the auditory processing system if listening to an audiobook. For vision-impaired students using Braille, the visual processing system is repurposed to process tactile input.)

- Word Recognition: The visual information of the letters and words travels to a part of the brain called the Visual Word Form Area (VWFA) located in the left fusiform gyrus. This area helps us to recognize words as whole units. With practice and exposure, readers become able to recognize words quickly and effortlessly, a process called orthographic processing.

- Phonological and Phonemic Processing: At the same time, your brain begins to decode the words, breaking them down into smaller units of sound, or phonemes. This is thought to involve regions such as Broca’s Area and the inferior frontal gyrus. This phonological processing is critical for new or unfamiliar words and is a fundamental skill that children learn when they are first taught to ‘sound out’ words.

- Semantic Processing: Once the words have been recognized and decoded, your brain works to understand their meaning in the given context. This involves regions such as Wernicke’s Area and the angular gyrus, which are involved in understanding the meanings of words and sentences.

- Integration and Comprehension: The meaning of each word needs to be integrated with the meanings of other words to comprehend the entire sentence or passage. This involves the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex and other regions associated with working memory, attention, and cognitive control.

- Making Inferences and Connections: Beyond literal comprehension, reading often requires making inferences, drawing conclusions, and connecting the text to your own knowledge and experiences. This involves a broader network of regions, including prefrontal areas involved in reasoning and decision-making and the medial temporal lobe, which is important for memory.

For fluent reading, all these processes must work together in tandem and nearly simultaneously. If there is a breakdown in any of the cognitive processes, readers will struggle to make meaning from text. Fluent reading also requires sustained attention and working memory capacity. All of this makes learning to read a challenging task, especially for students who have neurological differences (such as ADHD, dyslexia, or working memory dysfunction). Students require explicit instruction, extensive opportunity for practice, and wide exposure to various topics to build the background knowledge essential for comprehension.

The Science of Reading

The science of reading is not a single program. Rather, it is a body of research from various fields including psychology, cognitive science, linguistics, and education. The science of reading explores how we learn to read, what happens in the brain during reading, and which instructional approaches are most beneficial in helping students master reading.

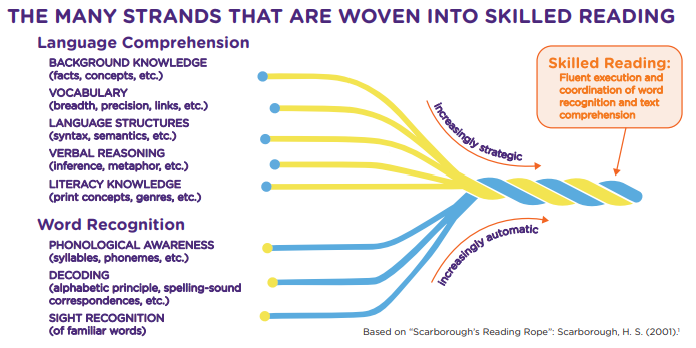

Dr. Hollis Scarborough, a senior scientist at Haskins Laboratories at Yale University and a leading expert in reading acquisition and dyslexia, developed a model for reading that has become a foundation for science-based reading instruction. “Scarborough’s Reading Rope,” first presented in 2001 in the Handbook of Early Literacy Research, provides a framework for understanding how all the strands of reading must be woven together to achieve fluency. The Reading Rope breaks down the reading process into two main strands, each with several sub-strands.

- Word Recognition Strands: These strands reflect the technical aspects of reading. They include Phonological Awareness (the ability to recognize and manipulate the sounds in spoken words), Decoding (mapping these sounds to their corresponding written forms/letters), and Sight Recognition (the ability to recognize words instantly without needing to decode them).

- Language Comprehension Strands: These strands involve the broader language and cognitive skills necessary for understanding the meaning of text. They include Background Knowledge, Vocabulary, Language Structures (understanding of syntax and semantics), Verbal Reasoning (the ability to think about and analyze language), and Literacy Knowledge (understanding the conventions of print and books).

Research has demonstrated that both major strands are equally important. We cannot focus strictly on word recognition (e.g., phonics) at the expense of the broader skills of language comprehension. Nor can we ignore the need of most children to have explicit instruction and practice in phonics and word recognition. The vast majority of children need instruction, practice and strategies for both word recognition and language comprehension.

Teaching Reading with Thinking Maps

As Scarborough’s Reading Rope demonstrates, learning to read is a complex task. So is aligning reading instruction with the science of reading. Even for teachers with extensive background in reading instruction, it can be difficult to address all of the elements of reading within the context of a busy classroom. It is even harder to provide the differentiation and individual attention many students need while they are learning to read.

Teachers need concrete, practical tools and strategies aligned with the science of reading. Thinking Maps can help. The eight Thinking Maps can be used in a variety of ways to support the development of reading skills, including both word recognition and language comprehension.

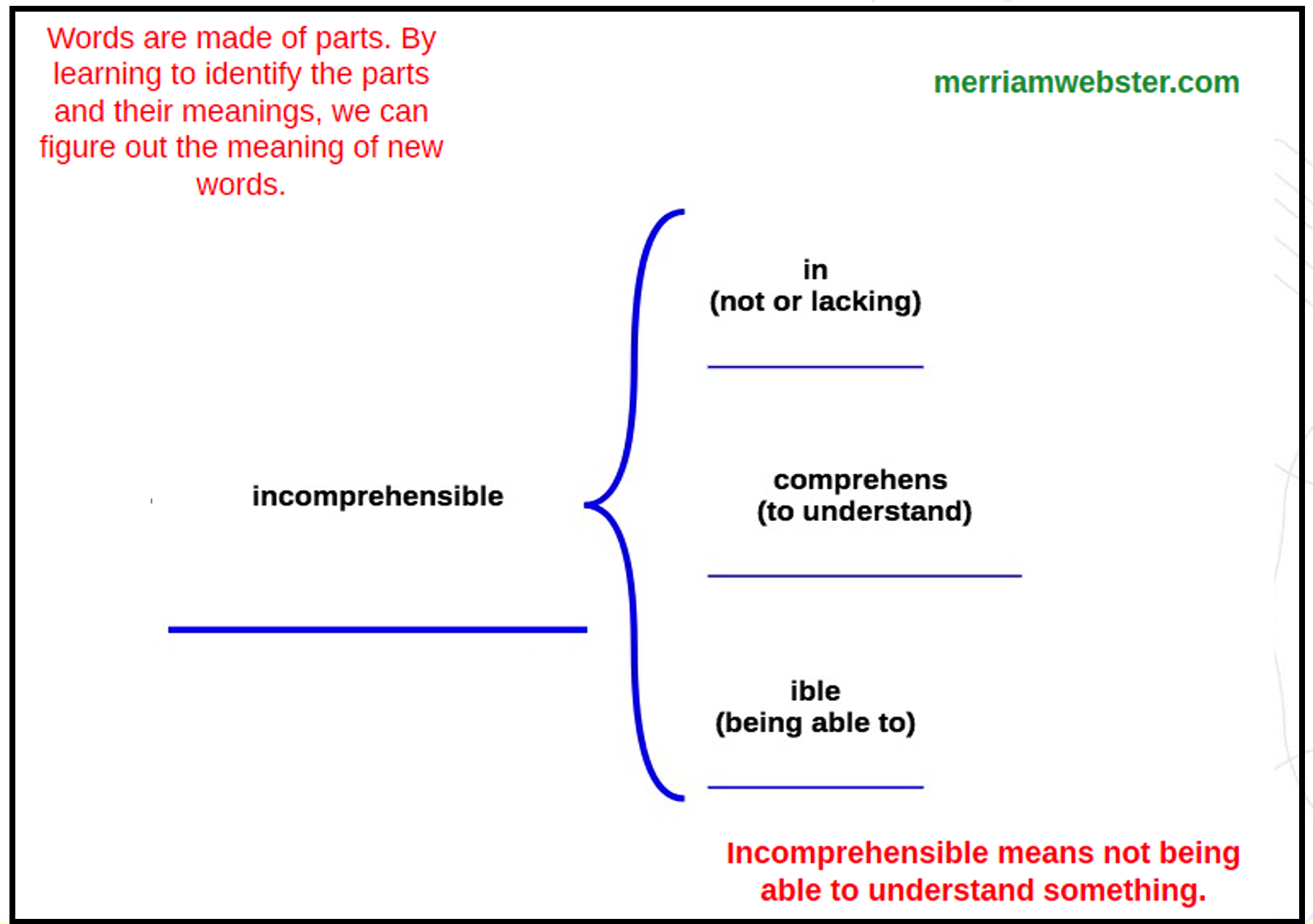

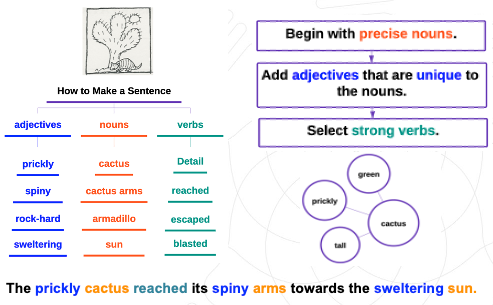

For example, the Brace Map can be used to break down parts of a word and develop verbal reasoning skills and vocabulary.

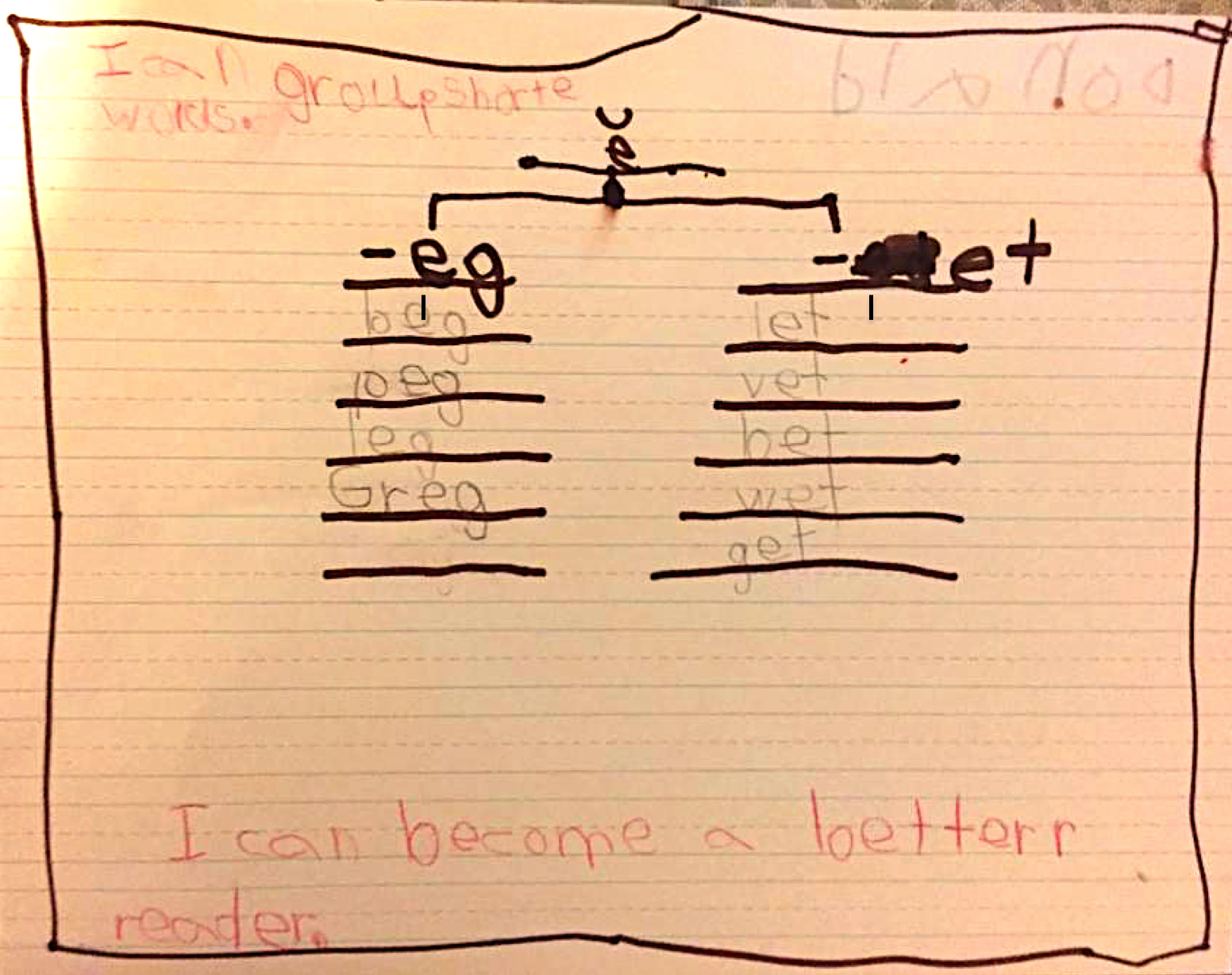

Classifying words by sounds and phonemes using a Tree Map helps to develop phonological awareness.

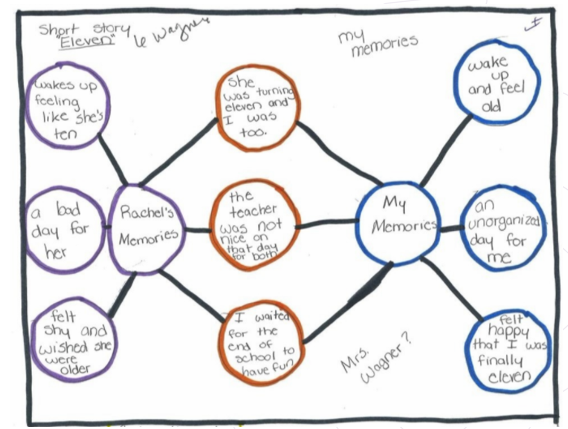

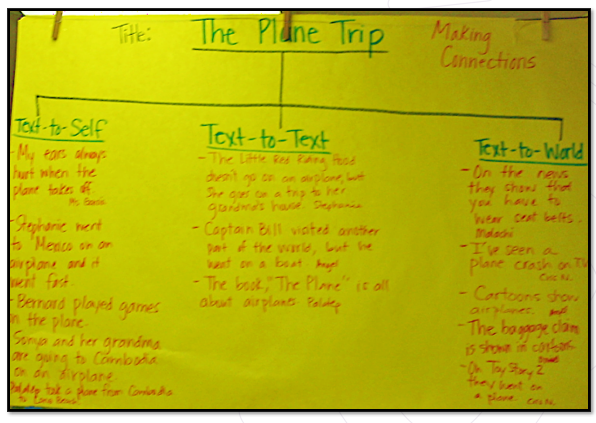

Thinking Maps can be used in a variety of different ways to help students analyze text, build background knowledge, and make connections.

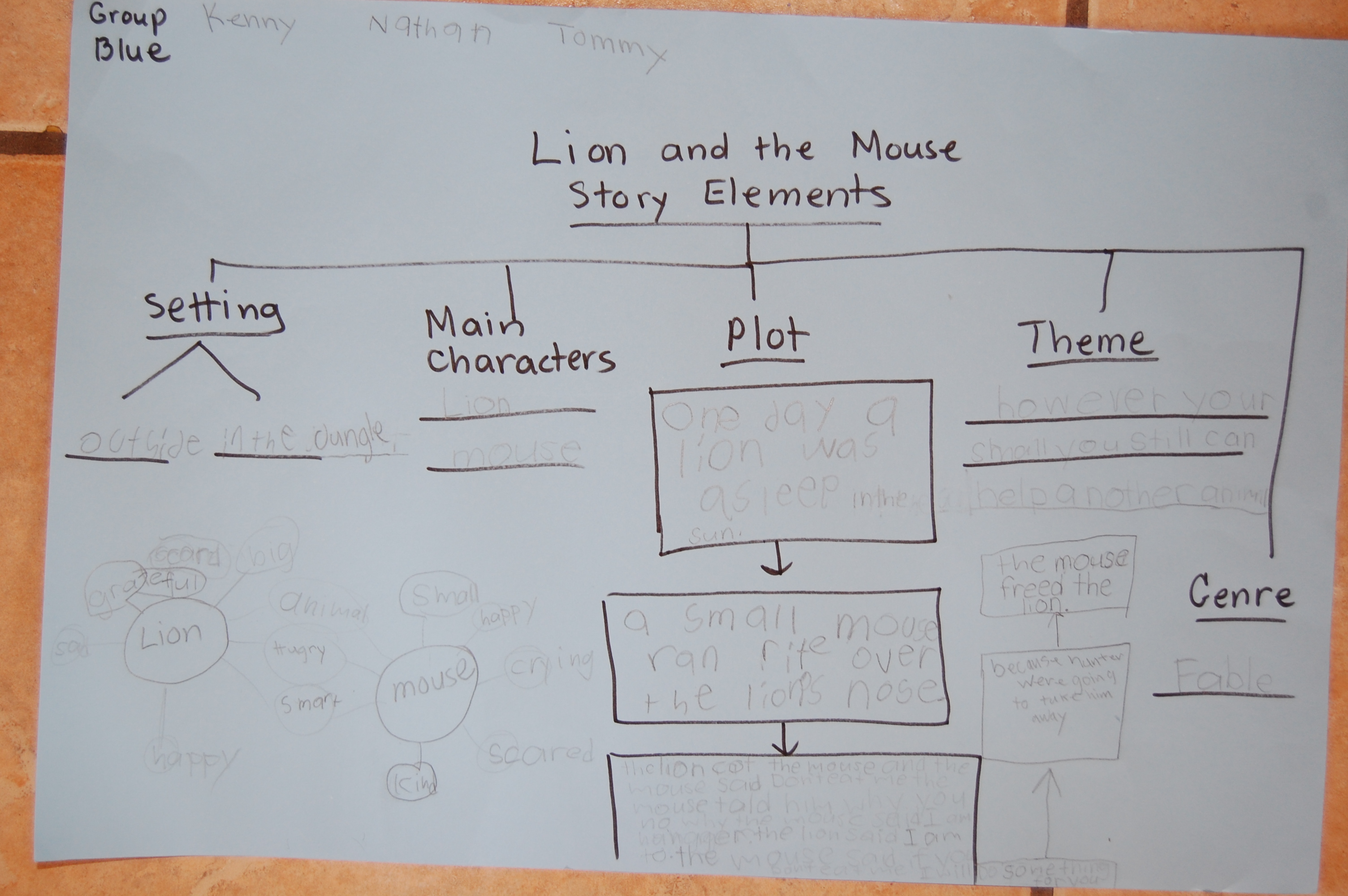

Students can use Thinking Maps to analyze sentences, paragraphs and entire texts to develop an understanding of literary structures.

Thinking Maps can be used at all levels of reading instruction to improve word recognition skills, vocabulary, verbal reasoning, and reading comprehension. By making the cognitive processes behind reading concrete and visible, Thinking Maps help students develop into fluent, confident readers.

Download the Science of Reading Alignment to learn more about how Thinking Maps Supports science-based reading instruction.

Continue Reading

September 14, 2023

Reading comprehension is the foundation for academic success across all subject areas. And yet, many students still struggle to engage deeply with written content and pull meaning from complex text. Here’s how teachers can support development of “deep cognitive structures” for reading comprehension that reduce the cognitive load so students can focus on content.

May 9, 2022

Many students struggle with writing. Giving students meaningful practice and clear structures for writing helps them move their thoughts out of their heads and onto the page.

April 12, 2022

Integrating reading strategies into science and social studies not only helps students grasp the content they are studying, but also builds the background knowledge students need to be better readers overall.

February 14, 2022

Teaching text structure is a powerful way to build reading comprehension skills. With Thinking Maps, we make text structure visible and explicit for students.