Reading for Understanding: Science and Social Studies

APRIL 12, 2022

Explicit instruction in reading comprehension strategies such as questioning, summarizing, and finding the main idea helps students draw meaning from text. But by itself, practice in comprehension strategies is not sufficient. Understanding complex expository text also requires grounding in content. Integrating reading strategies into science and social studies not only helps students grasp the content they are studying, but also builds the background knowledge students need to be better readers overall.

Teaching Content and Reading Simultaneously

Over the last several decades, much attention has been given to the problem of struggling readers. In 2019, only 35% of 4th graders and 34% of 8th graders scored at or above proficient on the NAEP. In spite of the heavy attention on reading skill development and intervention programs, this represents only a slight improvement since 1992, when 29% of students in each grade scored at or above proficient. At the same time, reading has taken up a larger and larger portion of the school day, often to the detriment of social studies, science and other content areas.

In fact, at the elementary level, time spent on science and social studies has plummeted in many schools. Students in elementary grades spend, on average, two hours a day on literacy instruction and less than 30 minutes each on science and social studies.

There is growing evidence that this approach may be backfiring—especially as students get older. In fact, some practitioners believe we have it exactly backward. Natalie Wexner, the author of The Knowledge Gap, argues in Chalkbeat:

“The most important factor in reading comprehension is not generally applicable skills like finding the main idea—it’s how much knowledge and vocabulary the reader has relating to the topic. So if we really want to boost reading comprehension, we should be doing the opposite of what we’re doing—especially in schools where test scores are low—which is cutting subjects like social studies and science that could actually increase students’ knowledge of the world.”

Another study by the Fordham Institute showed that spending more time on social studies instruction in the early grades—including history, civics and geography—produced greater gains in reading comprehension than reading instruction alone. Similar results have been found in science. What these studies point to is the importance of building background knowledge, vocabulary and context to support reading in the content areas. The results suggest that the best way to improve overall reading comprehension and set students up for success in higher grades may be to teach reading skills and subject-area content in tandem.

Building Vocabulary, Background Knowledge and Context

Supporting students with reading skill development within the content areas—using authentic and meaningful content—may be the most effective way to improve reading comprehension. Students who have broader background knowledge and vocabulary will have an important advantage when reading higher-level text in middle school, high school and beyond. Key strategies for reading in the content areas include activating prior knowledge, developing vocabulary, and building background knowledge. These strategies help students develop the context they need to effectively apply other reading strategies, such as questioning, making inferences or finding the main idea.

Students can use and apply Thinking Maps to help students build the content-area knowledge they need. For example:

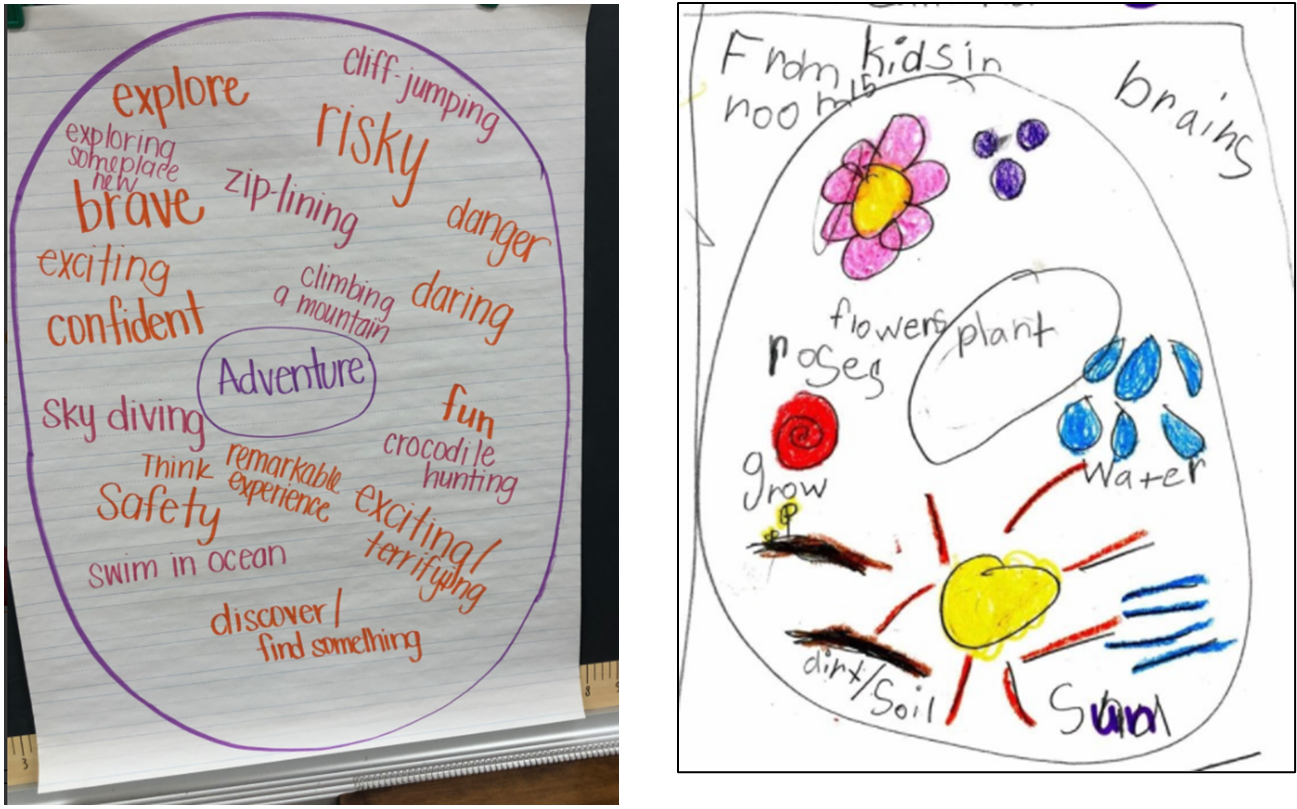

- Students can use Circle Maps to brainstorm what they already know about a topic or build new background knowledge.

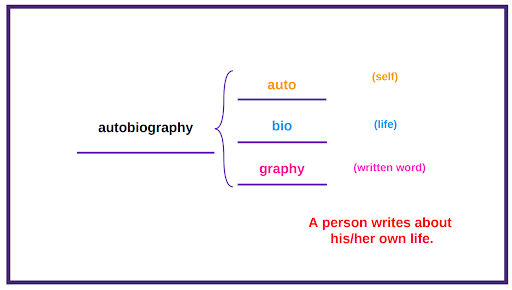

- For intensive vocabulary study, a Brace Map helps students break down words into their component parts to understand meaning.

Other Maps can be used in a variety of ways as students activate prior knowledge, build background knowledge and explore new vocabulary. Double Bubble Maps and Bridge Maps can be useful in connecting new learning to previous topics, for example. Students in Thinking Maps schools learn to use the Maps in a variety of ways throughout the learning process to deepen their understanding of new content and connect it to what they already know.

Teaching Discipline-Specific Reading Skills

Reading in the content areas also requires development of some thinking skills that are more discipline specific. While the eight types of thinking represented by the eight visual Maps each cross all content areas, some types of thinking are especially relevant for science and social studies. Using the Maps to activate these kinds of cognition helps students to “think like a scientist” or “think like a historian.”

Science Strategies: Classification and Part-to-Whole

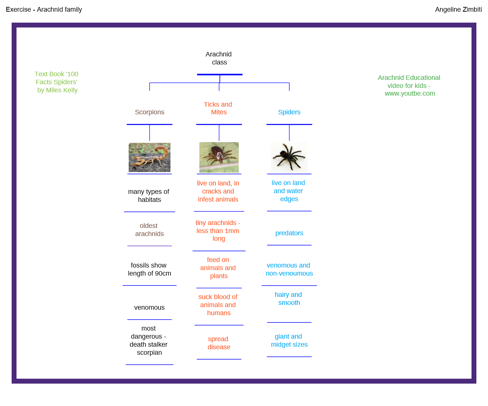

Classification is one of the essential skills for scientific thinking. Scientists learn to organize and group things in the natural world based on their attributes. Whether you are talking about animals, clouds, atoms or planets, the thinking is the same. Students must be able to create logical categories, determine the attributes that define each category, and sort items into categories based on the relevant attributes. Which Map is used for this type of activity? The Tree Map, of course.

Thinking Maps Learning Community (TMLC) members can find more strategies for teaching the skill of classification in TMLC Navigator: Classification—Teach and Practice. (For TMLC subscribers only.)

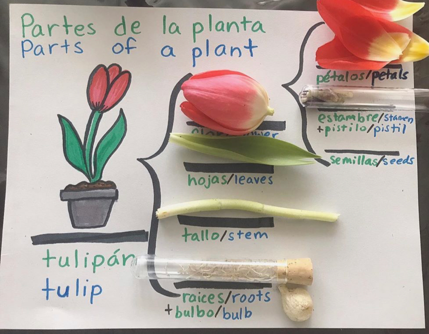

Scientists also explore the world by taking things apart to see how they work and how their component parts fit together. Learning how to apply “part-to-whole” thinking using a Brace Map is another essential scientific skill.

Social Studies Strategies: Sequencing and Cause-and-Effect

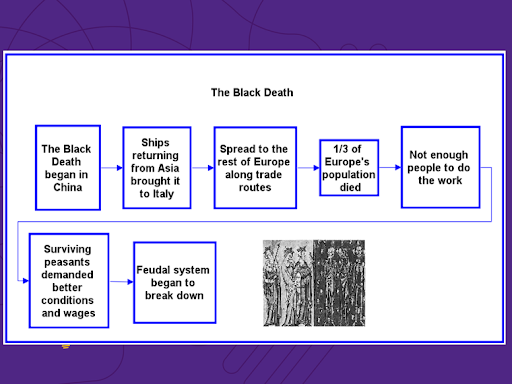

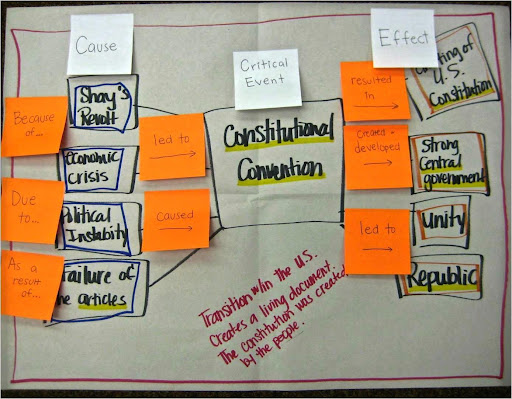

Historians, first and foremost, must be able to tell the story of history: what happened first? Then what? How did it end up? Putting events in order—sequencing—is one important way to understand history. The Flow Map helps students understand the order of events.

But historians want to know not only what happened but why it happened and how it impacted later events. For this kind of cause-and-effect thinking, the Multi-Flow comes into play.

TMLC subscribers can find additional resources for teaching cause-and-effect thinking in TMLC Navigator: The Complexity of Cause-and-Effect Thinking.

Thinking Across the Curriculum

Ultimately, students must be able to use all types of thinking in all content areas. Students in a Thinking Maps school learn how to use the Maps flexibly and fluently to engage deeply with grade-level content.

Implementing Thinking Maps in science and social studies does two important things.

- The Maps help students make sense of complex content in science or social studies and improve comprehension and retention of new information. This helps students build the background knowledge and vocabulary that become the basis of reading comprehension as they progress through the grades.

- As students apply the Maps, they are also honing critical reading skills such as sequencing, summarizing, questioning, and finding the main idea and details—skills that translate to better reading comprehension in any domain.

Learning new content and developing reading skills shouldn’t be mutually exclusive activities. With Thinking Maps, they don’t have to be.

Want to learn more about how Thinking Maps supports reading in the content areas? Contact your Thinking Maps representative to schedule a discovery session.

Continue Reading

July 2, 2025

A Meta-Analysis of studies showed that coaching, along with group training, curricular and instructional resources made a larger impact on the effects of teaching and student achievement.

June 16, 2025

At Thinking Maps, we are committed to creating a platform that not only meets but exceeds the expectations of our users. That’s why we’re thrilled to roll out a host of new user experience updates to the Thinking Maps Learning Community (TMLC). These updates represent a significant leap forward in usability, design, and functionality, ensuring a seamless and engaging experience for all users.

May 29, 2025

When it comes to professional learning for teachers, coaching has emerged as an effective method for fostering meaningful, long-term change in teaching practices. By offering personalized support, ongoing feedback, and practical application, coaching meets teachers where they are and provides the tools they need to thrive.

May 1, 2025

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming education, from custom content in a minute to personalized learning. But with this surge in AI adoption comes a critical challenge for educators and students alike—the need to strengthen critical thinking skills. While AI offers immense potential, it cannot replace the human ability to think analytically, question assumptions, and make independent judgments.