What Makes Writing So Hard?

MAY 9, 2022

Many students struggle with writing—but what makes it so hard? And why do so many students hate to write? Writing is a task with a very high cognitive load. Giving students meaningful practice and clear structures for writing helps them move their thoughts out of their heads and onto the page.

Who Needs to Write? Everyone.

Based on the most recent NAEP writing assessment, only about one in four students at any grade level is proficient in writing—and that number hasn’t shifted meaningfully in decades. One in five students scored at the lowest proficiency level, Below Basic, at each tested grade level. Clearly, the traditional English Language Arts (ELA) programs used to teach writing are not, on their own, enough to move the needle for most students.

At the same time, writing is more important than ever in our knowledge economy. Writing is a “gatekeeper” skill for many higher-paying professions. Most white-collar and technical jobs require at least basic writing skills, whether for creating formal reports or simply communicating through email. In blue-collar and service jobs, people are often expected to be able to write clearly to communicate with customers. And writing will almost certainly be required to advance beyond the entry levels. In fact, a survey of business leaders put written communication skills at the top of the list of sought-after attributes.

Beyond the workforce, writing, like reading, is a skill that enables full participation in our modern world. Good writing skills allow people to participate in democracy by writing letters to the editor or expressing their views to a representative. Writing also allows people to participate in, rather than simply watch, all of the discourse and entertainment happening online. Writing can empower people to self-advocate in a variety of contexts, from healthcare to consumer interactions to legal proceedings. Writing skills are essential for anyone who wants a seat at the table in today’s complex political, consumer and personal realms.

The High Cognitive Load of Writing

By some metrics, today’s kids and teens are writing more than ever—that is, if you count texting, commenting on online content, and interacting in multiplayer games. But these interactions do not rise to the level of writing required to be successful on state assessments, college assignments, or workplace tasks. When students are faced with an authentic writing task—such as responding to a piece of text, writing a research paper, or developing an original narrative—the majority struggle.

In part, that may be because students don’t have much practice with formal writing, especially in extended form. There is some evidence that students today spend less time on writing than in the past, especially on argumentative writing and writing in the content areas. The Institute of Educational Sciences (IES) recommends that students have 60 minutes of writing time each school day, including a mix of direct writing instruction and writing assignments that span different purposes and content areas. However, only about 25% of middle schoolers and 30% of high schoolers meet the standard, and many students are only spending about 15 minutes each day on writing.

But even with ample time and instruction, writing is hard—in fact, it is arguably the hardest thing we ask our students to do. Natalie Wexler, the author of The Knowledge Gap, explains that writing has an even higher cognitive load than reading. That’s because, in addition to processing information, students also have to figure out how to get their own thoughts on the page.

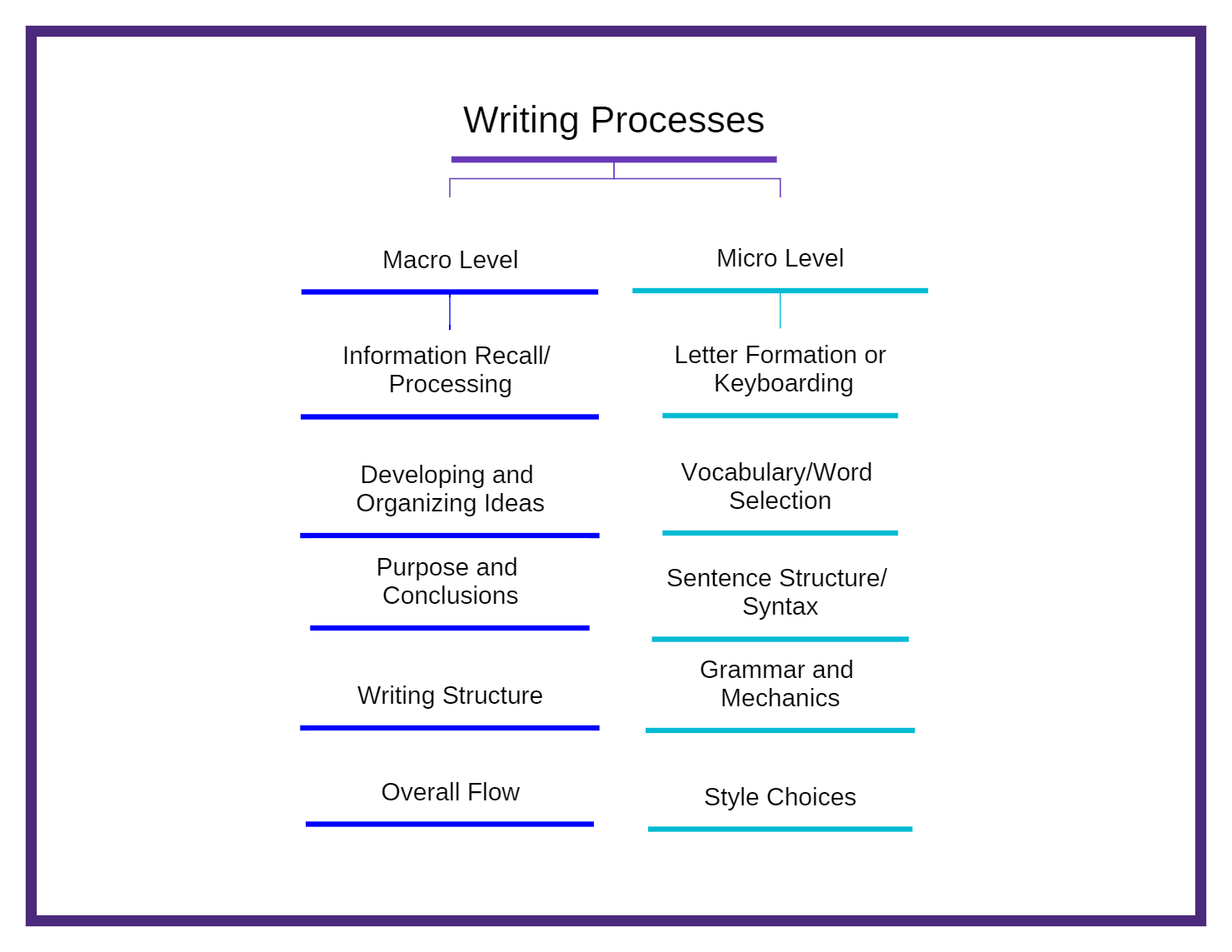

Writing is a highly complex skill that involves many discrete sub-skills at both the “macro” and “micro” levels.

- At the “macro” level, students have to figure out what to say: what is the point they are trying to make or the story they are trying to tell? What is the best way to organize their ideas and structure their piece? What are the big ideas and conclusions they want to get across? What kind of supporting evidence or details are needed?

- At the “micro” level, students must apply a myriad of foundational writing skills, from the motor skills involved with keyboarding or handwriting to decisions about word choice, syntax and grammar.

All of these writing processes are happening at the same time, adding to the overall cognitive load of the task. To lower the cognitive load, students must achieve proficiency and fluency at both the macro and micro levels. When students struggle with foundational skills such as letter formation and word selection, they may not have enough cognitive resources left to focus on the “big picture” of what they want to say. On the flip side, students who don’t know how to organize their ideas will not have much energy to focus on developing their writing style and editing and polishing their work.

The Hardest Part of Writing is Thinking

For most students, the hardest part of writing isn’t writing out individual words or forming a complete sentence. It is simply figuring out what to say. In fact, the Writing Center of Princeton says:

Writing is ninety-nine percent thinking, one percent writing. In other words, when you know what you want to say and how you want to say it, writing becomes easier and more successful.

Writing is, fundamentally, thinking made visible. If you can’t think, you can’t write. One of the best ways of lowering the cognitive load of writing is to give students a structure for organizing their ideas and thinking through the flow and structure of their piece.

That’s where Thinking Maps come in. Thinking Maps provide the structure for thinking through a writing task and organizing ideas prior to writing.

It starts with understanding the task itself. Students in a Thinking Maps school learn to use “signal words” that indicate what kind of thinking is required for a task. Then, they know what kind of Map to use to start their thinking process. For example, if the prompt asks them to explain the similarities and differences between two historical eras, they know immediately that this will be a “compare-and-contrast” task. The Double Bubble Map provides the structure they need to organize their ideas, whether from their existing knowledge, in-depth research, or a text provided with the prompt. Once they have fleshed out their ideas, students can use a writing Flow Map to develop their piece section by section. Having this kind of structure helps students move through the planning and organizing phases of writing more quickly so they have more time to spend on other parts of the writing process, including revising and editing. It also leads to clearer, more organized writing.

At Pace Brantley Preparatory, a Florida school serving students with learning disabilities in grades 1-12, adding some dedicated Thinking Maps planning time prior to writing led to better writing products on their benchmark assessments. Read the Pace Brantley story.

In our Write from the Beginning…and Beyond training, teachers learn how writing develops across the grade levels and how to use Thinking Maps to support student writing, including using the Maps to process thinking before writing and using the writing Flow Map to plan writing. Advanced training includes specific strategies for different genres, including Narrative, Expository/Informative, Argumentative, and Response to Text.

When students can think, they are ready to write. And when students can write, they are ready for anything.

Want to know more about Thinking Maps and writing?

Continue Reading

July 2, 2025

A Meta-Analysis of studies showed that coaching, along with group training, curricular and instructional resources made a larger impact on the effects of teaching and student achievement.

June 16, 2025

At Thinking Maps, we are committed to creating a platform that not only meets but exceeds the expectations of our users. That’s why we’re thrilled to roll out a host of new user experience updates to the Thinking Maps Learning Community (TMLC). These updates represent a significant leap forward in usability, design, and functionality, ensuring a seamless and engaging experience for all users.

May 29, 2025

When it comes to professional learning for teachers, coaching has emerged as an effective method for fostering meaningful, long-term change in teaching practices. By offering personalized support, ongoing feedback, and practical application, coaching meets teachers where they are and provides the tools they need to thrive.

May 1, 2025

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming education, from custom content in a minute to personalized learning. But with this surge in AI adoption comes a critical challenge for educators and students alike—the need to strengthen critical thinking skills. While AI offers immense potential, it cannot replace the human ability to think analytically, question assumptions, and make independent judgments.