Text Structure: The Key to Unlocking Informational Text

FEBRUARY 14, 2022

Every building you walk into has a structure to it that helps you understand how to navigate it and what its purpose is. The same is true for every piece of text. Just as doorways, hallways, rooms and stairways guide you through a building and reveal its purpose and attributes, the structure of a piece of text helps readers navigate through the details to extract meaning. That’s why teaching text structure is such a powerful way to build reading comprehension skills. With Thinking Maps, we make text structure visible and explicit for students.

How Understanding Text Structure Supports Comprehension

How do we know what to pay attention to when we read a piece of text? How do we organize the details of what we are reading into a framework for understanding? How do we determine the author’s purpose and make sense of the overall point they are trying to convey? The answers can usually be found by paying attention to the structure of the text. Effective writers structure their text in a way that supports their goals for their piece. Understanding text structure is the key to unlocking the meaning.

Early readers most often encounter text in the form of stories. Most stories follow a simple narrative structure which can be described as a sequence: first this happened, then that happened, and so on. But as students start reading more informational text, they will encounter additional and more complex text structures, such as comparison, cause-and-effect, problem/solution, description (or main ideas and details), and classification. Some texts may even have multiple text structures, such as cause-and-effect nested within an overall sequence of events.

Understanding the structure of a text improves comprehension by helping students organize big ideas and supporting details as they read, see how different pieces of information relate to each other, and get the “gist” (or main idea) of the entire passage. Without an understanding of text structure, students often struggle to make meaning and see how all the individual ideas fit together to make a whole. When asked to summarize or interpret a passage, these students may simply parrot back whatever details caught their attention without fully understanding the big ideas the author is trying to get across. When students can identify the text structure, they can use their understanding of that structure to construct meaning.

Four Text Structure Powerhouses for Reading Comprehension

Text structure may be explicit, but more often, it is implied. Good readers know how to analyze a piece of text to find the clues that tell them what kind of text they are reading. Is the author describing a sequence of events? Does the passage classify a set of things by their attributes? Does it show the causes or consequences of an event? Or does it simply describe or assert something and then provide supporting details?

There are many ways to organize informational text, but these four text structure powerhouses are among the most common.

- Sequence: This text structure presents an order of events. It shows what happened first, what happened later, and how things ended up. A historical narrative describing Magellan’s journey around the world might use a sequencing structure.

- Cause-and-effect: This structure is used to show the reasons something happened, the consequences of an event, or both. An economic analysis of the Great Depression could use a cause-and-effect structure to explain the events leading up to the Wall Street crash and the aftermath.

- Comparison and contrast: This structure shows how two or more things are similar and how they are different. For example, an author might describe the shared attributes of plant and animal cells and the unique characteristics of each.

- Main ideas and details/classification: This is a common structure for describing something. A writer describing the Taj Mahal might start with a general explanation of what the building is and then dig into pertinent details about its construction. Or, a writer might describe the attributes of various building types.

To identify the text structure, students can start by asking two important questions.

- What question is the author answering? This is another way of thinking about the author’s purpose. Perhaps they are describing how to bake a cake (a sequence). Or maybe they are explaining the consequences of a piece of legislation (cause-and-effect). When students identify the question the author is answering, they are identifying the main idea of the piece and the author’s purpose for writing it.

- What signal words can be identified in the text? Scanning the text for signals words such as “next,” “because,” “for example,” or “on the other hand” will also provide clues to the structure of the text.

Building Better Readers by Mapping Text Structure

Thinking Maps give students a framework for understanding and analyzing text structure. They also act as a guide when students are taking notes from a text. For students in Thinking Maps schools, looking for signal words and organizing complex ideas into logical patterns becomes second nature.

For example, consider the following text.

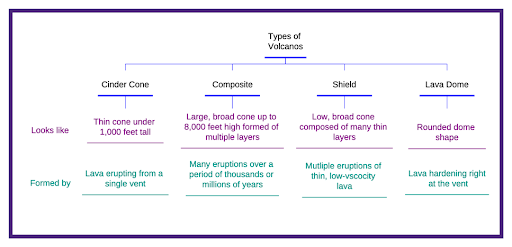

There are four main types of volcanos. They can be classified by how they are formed and the size and shape of the resulting mound. A cinder cone volcano looks like a thin cone and is usually under 1,000 feet tall. It is shaped by lava that erupts from a single vent at the top of the cone. A composite volcano is also cone-shaped, but it is shaped from multiple events over thousands or millions of years. These volcanos can be up to 8,000 feet high and are formed of many thick layers of lava. A shield volcano is a broad, low cone composed of many wide, thin layers of lava that are laid down by multiple eruptions of thin, low-viscosity lava, which travels farther before it cools. And lava domes are created when lava hardens right at the vent, forming a rounded dome shape.

A Thinking Maps student immediately recognizes this as a classification exercise based on keywords like “types” and “classified.” Now that they know the text structure, they know what they are looking for: different types of volcanoes. And there they are—cinder cone, composite, shield, and dome, each with some supporting details behind it. Students also know exactly which Map they should use to organize information they take out of the passage: the Tree Map.

Thinking Maps also help students analyze complex texts with multiple nested structures. For example, a textbook chapter on the Great Depression may have an overall organization of Sequencing. A Flow Map would be used to show the order of the major stages of the Depression and the individual events (sub-stages) that take place within each stage. But within the chapter, individual sections or passages may have a cause-and-effect structure, showing what led up to and resulted from individual events. Multi-Flow Maps would be used to analyze these causes and effects.

Students also learn how to take information back off the Map to generate their own writing. The Maps become the basis for their written summary, retelling or explanation. By creating the Map, students are solidifying their understanding of the information in the text. They can now take information back off the Maps and combine it in various ways to create their own unique learning products. Want to know more about using Thinking Maps to analyze text structure? Thinking Maps Learning Community (TMLC) users can check out the Text Structures training module (course 303), along with our Navigator Series on text structures. In February, Navigator focused on Comparison and Contrast; in the coming months, we’ll explore identifying causes and effects, categorizing and sequencing.

Not a TMLC subscriber? Talk to your Thinking Maps representative to unlock your access!

Continue Reading

July 2, 2025

A Meta-Analysis of studies showed that coaching, along with group training, curricular and instructional resources made a larger impact on the effects of teaching and student achievement.

June 16, 2025

At Thinking Maps, we are committed to creating a platform that not only meets but exceeds the expectations of our users. That’s why we’re thrilled to roll out a host of new user experience updates to the Thinking Maps Learning Community (TMLC). These updates represent a significant leap forward in usability, design, and functionality, ensuring a seamless and engaging experience for all users.

May 29, 2025

When it comes to professional learning for teachers, coaching has emerged as an effective method for fostering meaningful, long-term change in teaching practices. By offering personalized support, ongoing feedback, and practical application, coaching meets teachers where they are and provides the tools they need to thrive.

May 1, 2025

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming education, from custom content in a minute to personalized learning. But with this surge in AI adoption comes a critical challenge for educators and students alike—the need to strengthen critical thinking skills. While AI offers immense potential, it cannot replace the human ability to think analytically, question assumptions, and make independent judgments.