Thinking About Thinking: Why Metacognition Matters

FEBRUARY 13, 2019

How do you help students build metacognitive skills?

Metacognitive skills are a predictor of success in the classroom and beyond. Students who are able to access their own cognitive processes and reflect on what and how they are learning are able to learn more effectively.

For some students, metacognitive thinking seems to come naturally. But most need a little help to peek inside their own brains. Fortunately, metacognitive skills can be taught and developed, just like any other skill.

What We Mean by Metacognition

Metacognition means "thinking about thinking." Taken from the root words meta, meaning "beyond," and "cogito," meaning "thinking," metacognition is the ability to observe and reflect on our own cognitive processes. It's the little voice inside your head that says things like "wait…do I really understand that, or do I need to read it again?" or "does this problem remind me of anything else I already know?"

Metacognition is believed to be a uniquely human capacity. Thanks to a highly developed neocortex, humans are able to turn their observational powers inward to think about what they know, what they need to know, and what strategies they can apply to solve a problem. Metacognition is what enables humans to step back and think through problems rather than simply reacting instinctually. Our metacognitive processes allow us to learn from prior experiences, generalize learning so we can apply strategies to new situations, evaluate the utility of different approaches, and decide how we might do things differently next time.

These skills are critical in the classroom. Students with good metacognitive skills are able to plan an approach to learning a new skill or solving a problem, monitor their progress towards their goal, and evaluate their own success. They can analyze both the requirements of the task and their own knowledge base and skill set to decide on an effective approach and determine what else they need to learn to be successful.

A Peek Inside the Metacognitive Classroom

While all humans are capable of metacognition, not all of us use metacognitive strategies effectively. Educational researcher Art Costa estimates that only one half to two thirds of adults are fluent in metacognition.

This may be because most learning standards are focused more on what students should learn rather than how they learn. Metacognitive skills must be explicitly taught in the classroom if we want students to develop them. It's not enough to tell students to "think about it." We need to teach them how to think, and how to access their own thinking processes.

Teaching metacognitive strategies must happen in the context of the content that they are learning. These skills cannot be taught in isolation. Instead, teachers should integrate metacognitive strategies with all of the content-based lessons they are teaching. Explicitly teaching metacognitive skills can help teachers close the gap between struggling students and high achievers, who are often the students already applying metacognitive strategies.

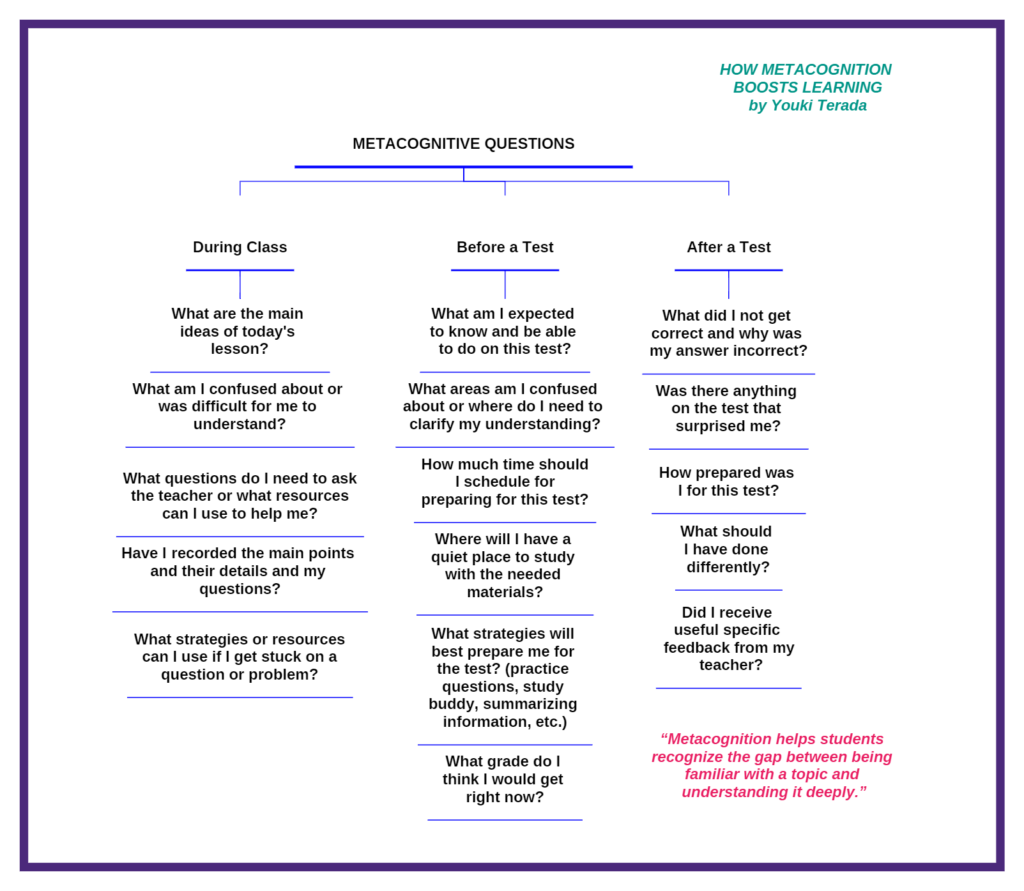

One way to stimulate metacognitive thinking is by asking metacognitive questions and teaching students to ask these questions themselves. Students who learn how to ask the right questions during the learning process will be able to monitor and evaluate their own learning in real time. The Tree Map below, which pulls from Youki Terada's Edutopia article, lists some questions students can ask themselves before, during, and after a learning task or test.

Building Metacognitive Skills with Thinking Maps

Another way to build metacognitive skills is to make thinking visible for students. Thinking Maps allow students to visualize cognitive processes. Each of the eight Maps is tied to one of our fundamental cognitive process: defining in context, describing, comparing/contrasting, classifying, part/whole relationships, sequencing, cause & effect, and analogies. When students create a Thinking Map, they are able to access these cognitive processes more easily. It's like getting a look "under the hood" in their own brains.

Thinking Maps also incorporate a "Frame of Reference" that helps students think more deeply about where their information comes from, the different perspectives that influence their thinking, and the conclusions that they can draw from what they have learned.

Students who use Thinking Maps learn to recognize the academic vocabulary that is linked to each of the core cognitive processes. This helps them quickly analyze a task to see what is being asked and determine which mode of thinking is required to tackle the problem. As students become proficient with the Maps, they learn how to activate and apply cognitive processes to become more effective learners and thinkers.

Download Our Metacognition Issue Brief!

For Further Reading and Viewing

- How Metacognition Boosts Learning (Terada)

- Metacognition: What Makes Humans Unique? (Costa, Kallick)

- Do Your Questions Invite Metacognition? (Costa, Kallick)

- Video: Habits of Mind—Metacognition (Costa)

- Video: Metaphor and Metacognition (Ivy)

Continue Reading

April 12, 2023

Asking better questions is an important component of critical thinking. Learn how to go beyond the "Five Ws" to ask questions that promote higher-order thinking.

November 8, 2021

The perceived difficulty of a task is known as the “cognitive load.” We can lighten the load for students by helping them develop cognitive habits that automate thinking skills, so they can focus on content.

September 13, 2021

During the Assess phase of the Professional Development cycle, teachers look at the outcomes that they have achieved and determine whether or not the application was effective.

August 9, 2021

Application is a critical step in the Professional Development cycle. To facilitate lasting change in the classroom, teachers must be able to apply what they have learned.