Lightening the Cognitive Load

NOVEMBER 8, 2021

What makes a task feel easy or hard? The perceived difficulty of a task may be explained in large part through the concept of “cognitive load.” When a task exceeds the capacity of our limited working memory, it may feel difficult or impossible to complete. We can lighten the load for students by helping them develop cognitive habits that automate thinking skills, so they can focus on the new concepts that they are learning. Thinking Maps helps students develop deep structures for critical thinking that reduce the cognitive load of rigorous assignments.

Working Memory and Cognitive Load

Cognitive load theory was first developed by John Sweller, an Australian educational psychologist, in 1988, building on Baddeley and Hitch’s (1974) “working memory” model of learning. In Sweller’s theory, the “cognitive load” of a mental task refers to the amount of working memory resources required to complete the task. Sweller proposed that learning could be made more effective through instructional design that reduces cognitive load.

To understand what he means, let’s first take a closer look at working memory. Working memory is part of the executive functioning system of the brain. It is used to temporarily store and manipulate information that we are currently using for a task. It also organizes information for storage in long-term memory (in other words, it puts information into a schema). If concepts remain jumbled in working memory, they will be misremembered or not remembered at all. Many learning disabilities and executive function disorders are related to problems with the working memory system.

Working memory is highly limited; most experts believe that it can hold between four and seven “chunks” of information (e.g., digits, letters, words) at a time. We augment this limited working memory by tapping into things already stored in our long-term memory. Learning involves a constant interplay between the working and long-term memory systems.

When a task requires us to use the maximum capacity of our limited working memory, we say it has a high cognitive load. If the cognitive load is too high—that is, if the task requirements exceed our working memory capacity—we will not be successful. Effective instructional design matches the task to the cognitive capacity of the learner to ensure that the cognitive load is appropriate for growth without overloading the student.

Types of Cognitive Load (and How to Reduce Them)

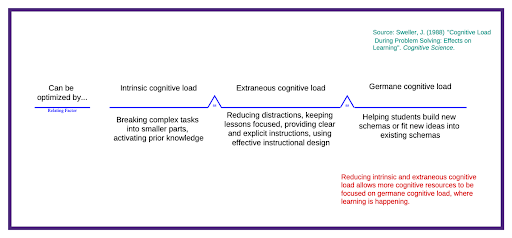

Cognitive load is generally divided into three types: intrinsic, extraneous and germane. Each type of load has different methods for reduction or optimization.

- Intrinsic cognitive load refers to the inherent difficulty level of the task itself. The difficulty level of a task for an individual will depend in large part on their prior knowledge and familiarity with the topic. The intrinsic load of a task can be reduced by breaking a complex task into smaller parts and activating prior knowledge prior to introducing a novel concept.

- Extraneous cognitive load is a function of how the material is presented, including the format (e.g., visual vs. verbal), the instructions, and the amount of extraneous information students must process. The instructional design of a lesson may either lessen or heighten the cognitive load of the learner. Classroom distractions such as excess noise or intrusive visual stimuli can add to the extraneous load, as students must spend precious working memory processing and filtering out this sensory input. Confusing instructions and distracting information that is not necessary for the lesson also add to extraneous load. Teachers should make every effort to reduce extraneous cognitive load in their lessons. This can be accomplished by limiting distractions in the classroom, keeping lessons focused, presenting instructions clearly, and using effective instructional design in the presentation of material.

- Germane cognitive load is related to the building of memory schemas for organizing and interpreting information. This is the “good” kind of cognitive load—productive mental processing that leads to learning. A memory schema refers to the way we conceptualize concepts in long-term memory. It may be a routine that we follow, a category that we place people or objects into, or a framework for thinking about events, relationships or patterns of behavior. Learning involves continually building new schemas or fitting new information into our existing schemas so they become more nuanced, accurate and precise over time. Helping students deliberately activate and interrogate their existing schemas and showing them where new information fits into these schemas can make learning more effective.

Developing Habits of Thinking to Reduce Cognitive Load

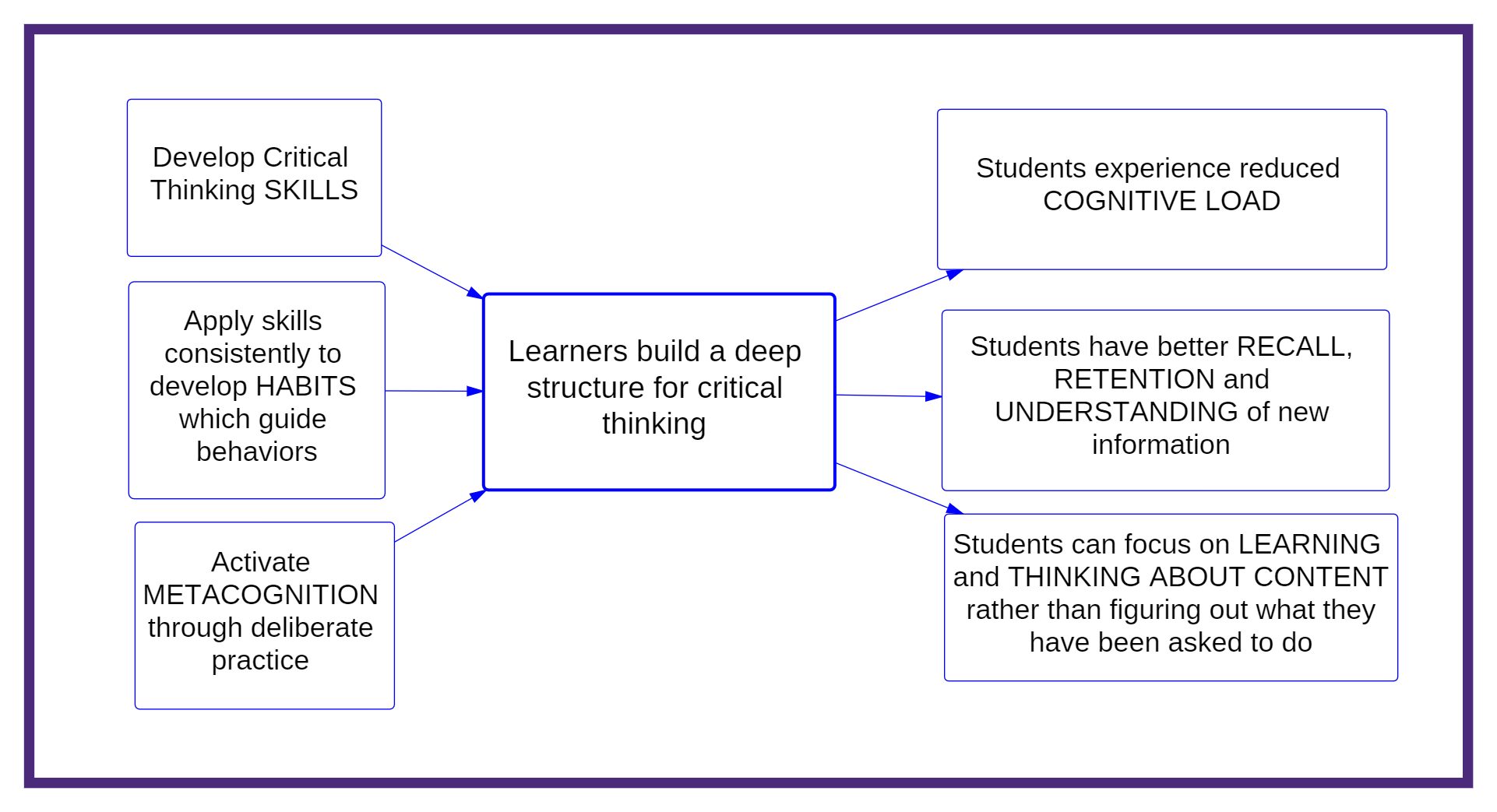

Cognitive load is highly interconnected with critical thinking. When students have better critical thinking skills, the cognitive load for a task is reduced.

Rigorous academic tasks involve both the content (the material we want them to learn or use) and what we want students to do with that content (apply, evaluate, compare, explain, etc.). Students must be able to understand both the material and the kind of thinking that we are asking them to do. If students lack an understanding of the academic vocabulary and critical thinking skills required for the task, they spend too much mental energy trying to figure out what they are supposed to do instead of thinking about the material. In other words, their limited working memory is taken up by figuring out the instructions and parameters of the task, and there isn’t enough left over for schema building. This is one aspect of the cognitive load problem in action.

This is where having a deep structure for critical thinking can help. A deep structure for critical thinking allows students to:

- recognize the kind of thinking they are being asked to do based on the kinds of academic vocabulary in the prompt (e.g., describe, compare and contrast, explain the steps, determine the impact), and

- activate the higher-order thinking skills required by the task.

By explicitly teaching these critical thinking skills, we help students develop the habits of thinking that will allow them to be successful. As students develop a structure for critical thinking, these skills become automated, reducing the cognitive load for completing the task. Automating thinking skills allows students to spend their mental energy on the content instead of the instructions for the task.

Thinking Maps and the Cognitive Load Problem

Thinking Maps helps students develop these cognitive habits by making thinking skills visible and concrete for students. As students learn to match academic vocabulary to the eight types of Maps, they are learning how to activate the right kind of thinking for practically any task. Over time, these habits become fully automated. For example, if students encounter a task with terms like “explain the impact of…”, “what led to..?”, or “identify the outcomes of…”, they know that they are facing a Cause and Effect task that can be visualized using a Multi-Flow Map. Organizing their ideas in the Multi-Flow automatically activates the right kind of thinking for the task. The Map helps the student deepen and demonstrate their understanding of the content and can be used as a basis for a formal written product or presentation.

The more students work with the Maps, the more they understand their own cognitive processes and how to activate the right process for any assignment. They even learn how to use multiple Maps for complex assignments requiring many types of thinking. Using the Maps consistently over time develops the deep structures for critical thinking that are required for academic success and lifelong learning. In turn, these deep structures for thinking lessen the cognitive load, allowing students to tackle complex, rigorous assignments and incorporate new learning into their existing schemas.

Ready to learn more about Thinking Maps? Contact your Thinking Maps representative.

Continue Reading

July 15, 2024

"Initiative overload" can cause teachers and school leaders to lose sight of the fundamental practices that have the greatest impact on their goals and mission. When this happens, it's time for a reboot.

May 16, 2024

Mastering Science Concepts and Content in K12 | Thinking Maps Support student mastery of the Core Ideas and Crosscutting Concepts in the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) with Thinking Maps. Learn more on the blog:

April 15, 2024

Scientific thinking empowers students to ask good questions about the world around them, become flexible and adaptable problem solvers, and engage in effective decision making in a variety of domains. Thinking Maps can help teachers nurture a scientific mindset in students and support mastery of important STEM skills and content.

February 15, 2024

A majority of teachers believe that students are finally catching up from pandemic learning losses. But those gains are far from evenly distributed—and too many students were already behind before the pandemic. To close these achievement gaps, schools and districts need to focus on the underlying issue: the critical thinking gap.