Mastering Scientific Concepts and Content

MAY 16, 2024

The Next-Generation Science Standards* (NGSS) are divided into three areas: Core Ideas (discipline-specific knowledge), Practices and Cross-Cutting Concepts. Last month, in Thinking Like a Scientist, we discussed how Thinking Maps can support the development of scientific practices, including critical and creative thinking, collaboration and communication, and applying modeling and mathematics. However, scientific thinking must also include a solid grounding in content-area knowledge and general scientific concepts. Thinking Maps can help here, too.

What Are Cross-Cutting Concepts?

Cross-cutting concepts are big ideas that help students make sense of scientific information across disciplines. These concepts provide a framework that unifies different scientific disciplines, making learning more integrated and meaningful. They include seven key themes that apply universally:

- Patterns: Noticing patterns helps to identify trends (like animal migration routes or repeating weather patterns), relationships, and similarities and differences between phenomena.

- Cause and Effect: By understanding the relationship between actions and outcomes, students can predict consequences, such as the effects of pollution on ecosystems.

- Scale, Proportion, and Quantity: Students grasp the importance of measurements, helping them understand concepts ranging from microscopic cells to astronomical distances.

- Systems and System Models: Viewing natural and engineered systems allows students to see how parts work together, like the water cycle or a car engine.

- Energy and Matter: Students understand that energy and matter are conserved and transferred in ecosystems, chemical reactions, and machines.

- Structure and Function: Recognizing that the form of an organism or object suits its function, like bird beaks adapted to specific food sources.

- Stability and Change: Identifying consistent patterns and shifts over time helps students predict natural phenomena or technological changes.

Thinking Maps are well suited to these types of thinking. In fact, many of them correlate directly to these cross-cutting concepts.

Patterns

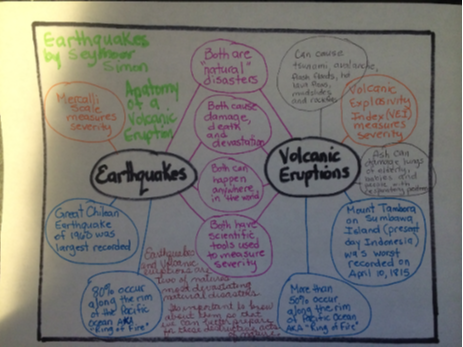

There are many kinds of patterns, each of which can be expressed with different types of Thinking Maps. The Double Bubble Map allows students to explore patterns in terms of similarities and differences.

Cause and Effect

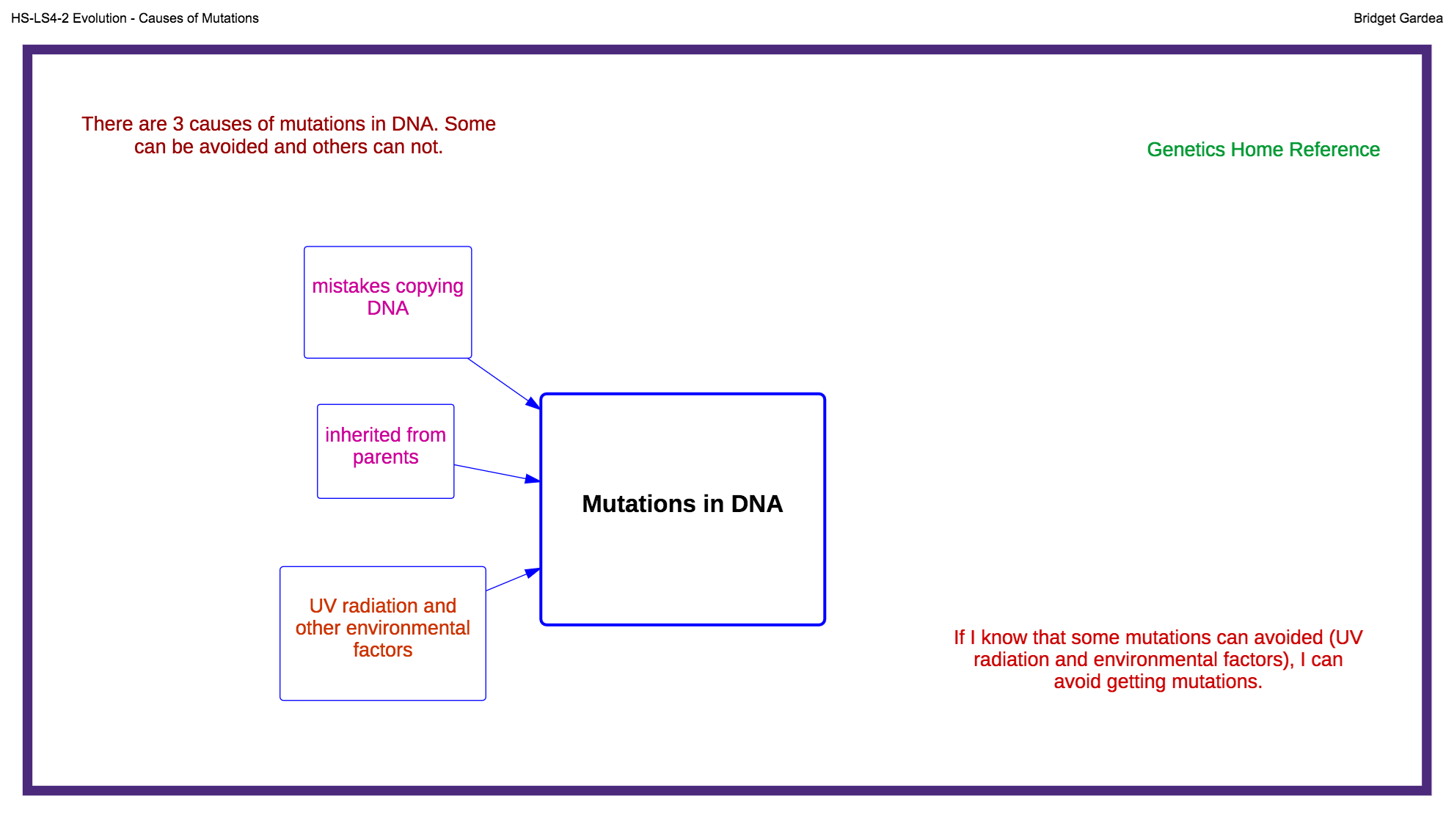

The Multi-Flow Map is all about cause-and-effect thinking.

Scale, Proportion and Quantity

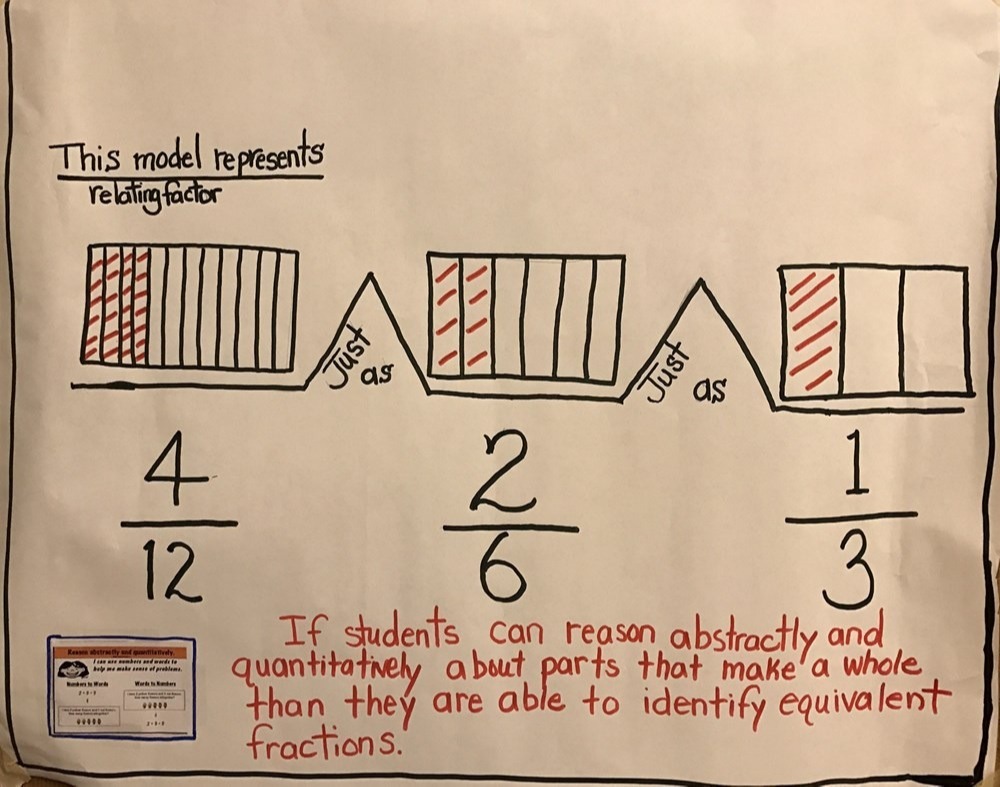

This Bridge Map is a great way to help students visualize proportions and quantities.

Systems and System Models

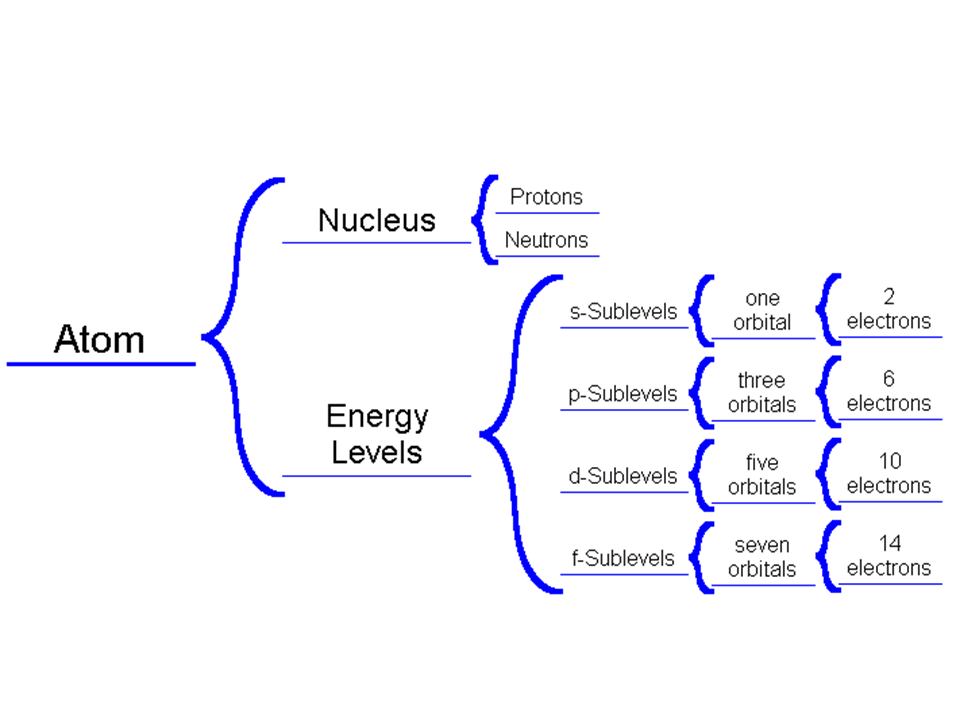

Systems and models require an understanding of part-to-whole relationships, which can be expressed in a Brace Map.

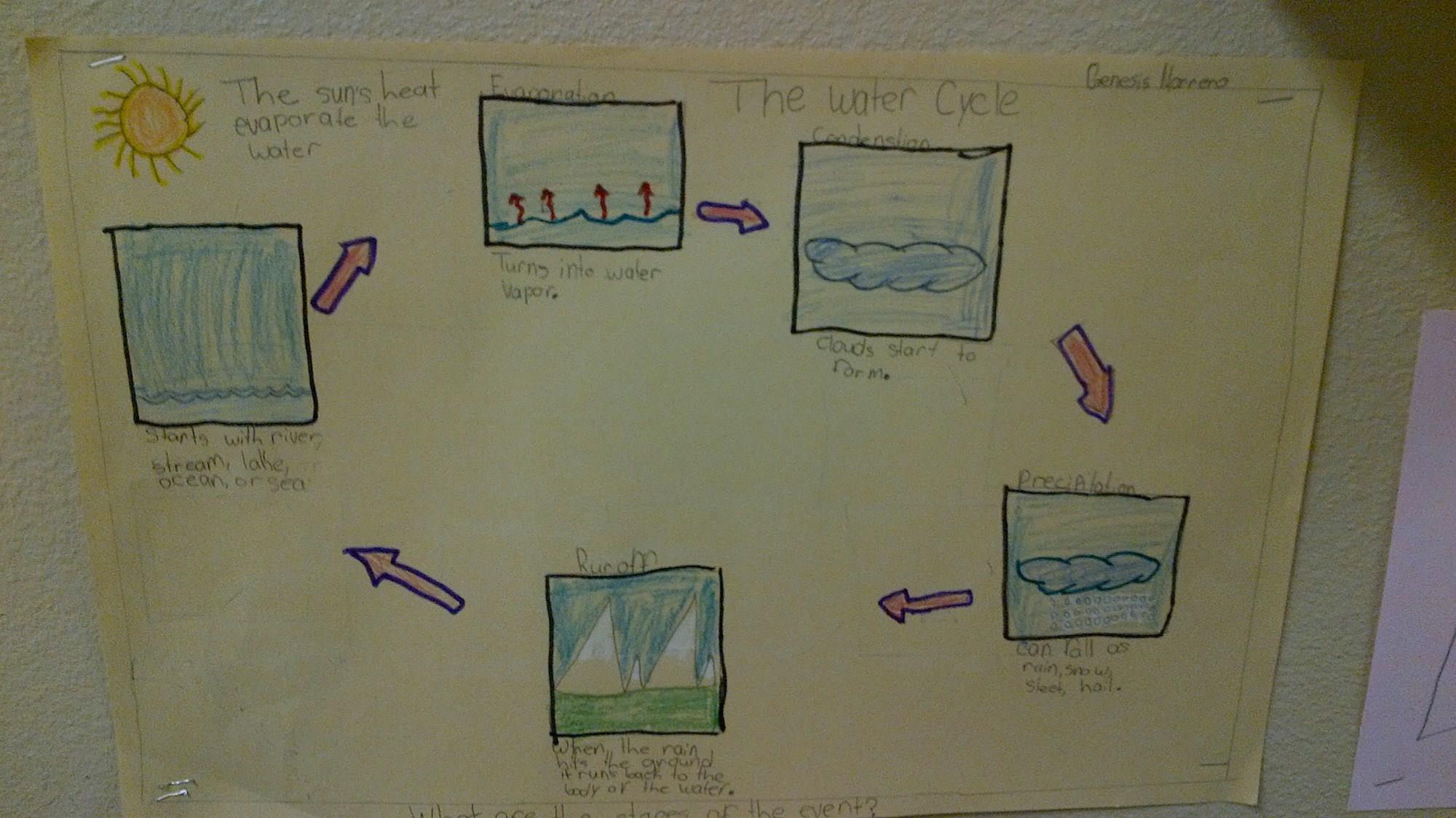

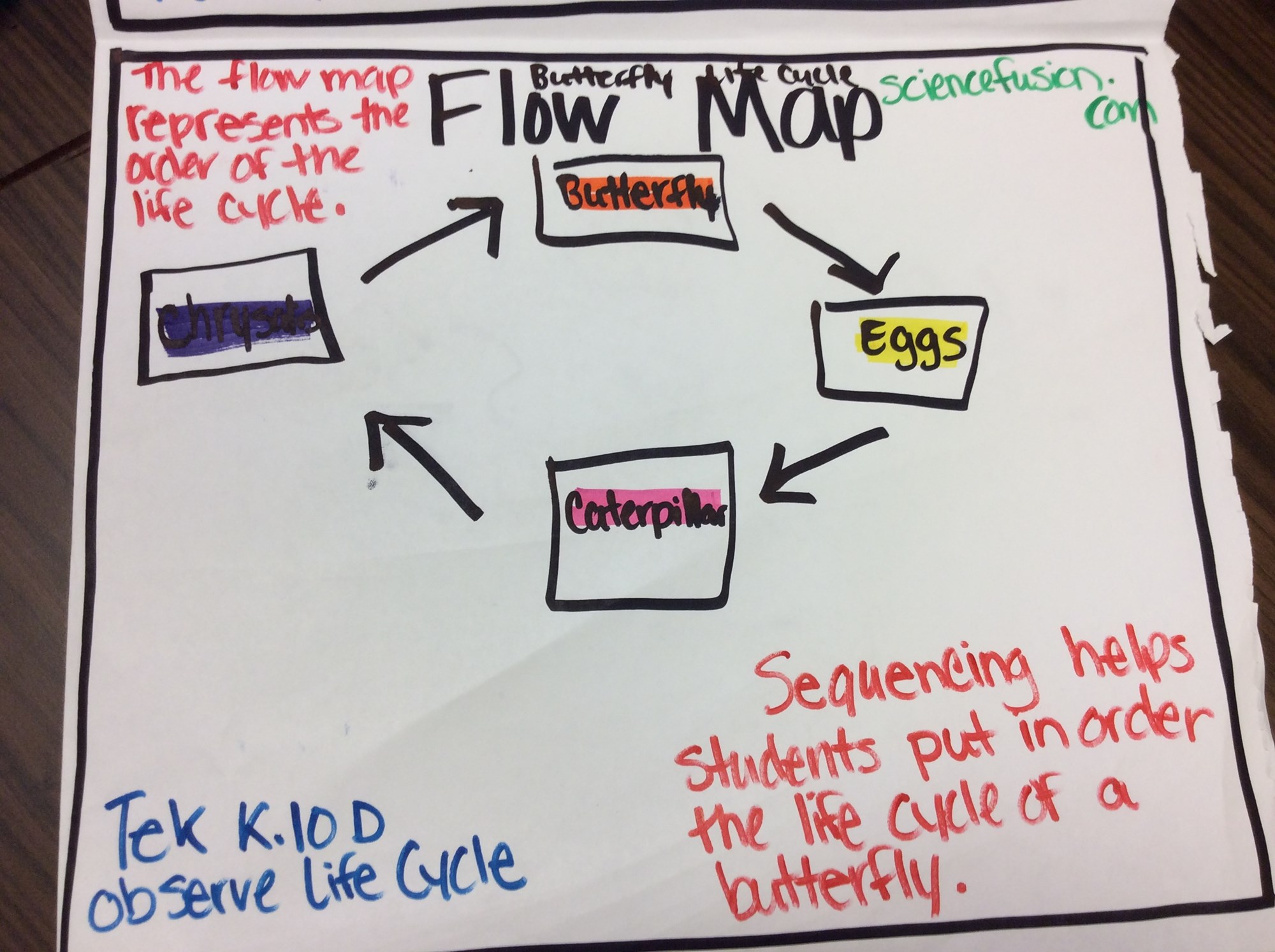

Other types of systems, like the water cycle, may be better expressed as a Flow Map.

Energy and Matter

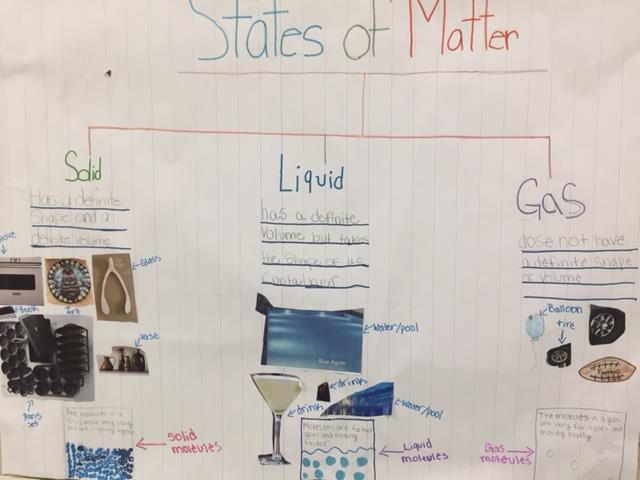

Students can use a Tree Map to classify states of matter and forms of energy.

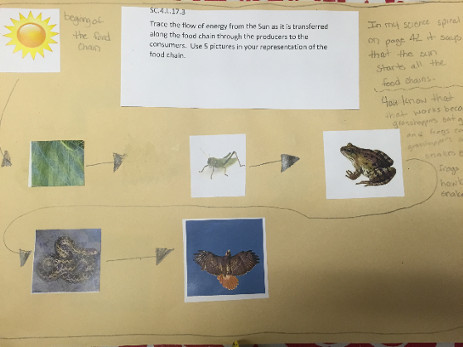

Transformations can be expressed using a Flow Map.

Structure and Function

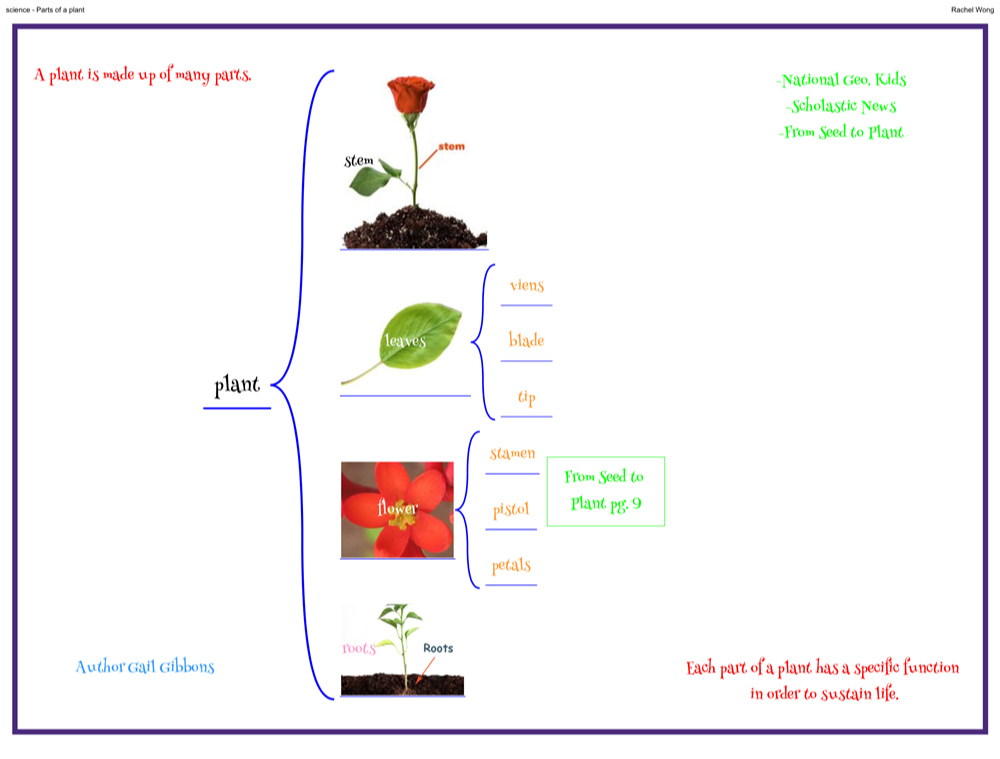

The Brace Map can be used to explore structure and function in terms of Part-to-Whole relationships.

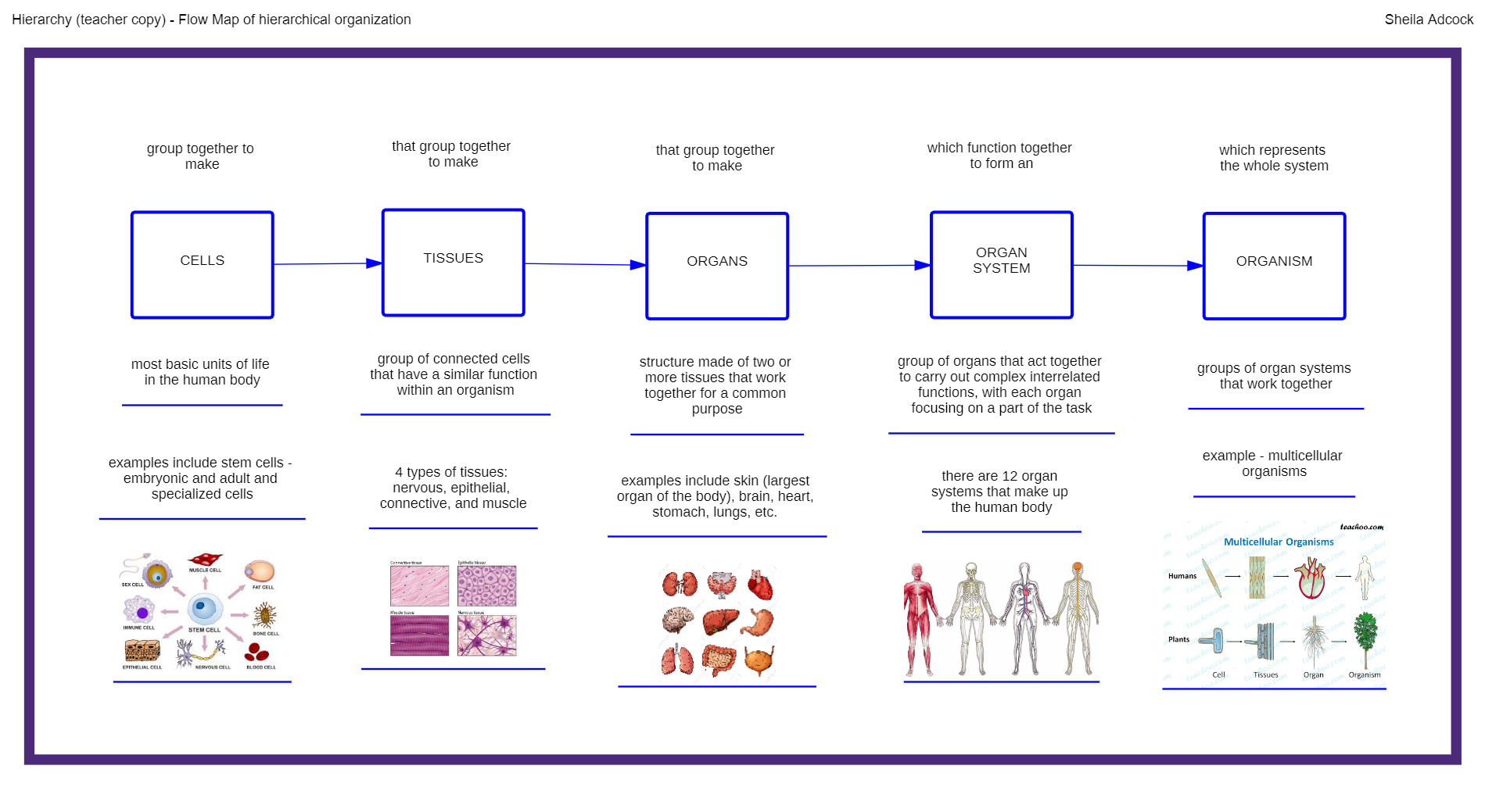

This Flow Map was used to explore hierarchies of body systems.

Stability and Change

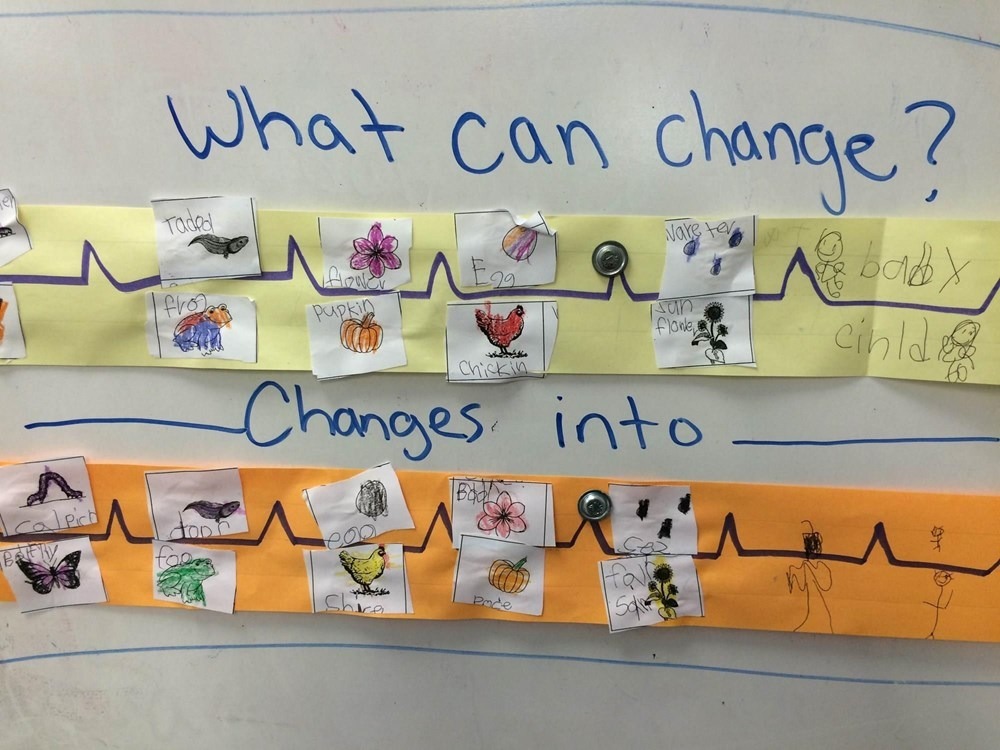

This Bridge Map is a great way to explore change.

A Flow Map might be used to show the sequence of changes.

Core Ideas: The Basis for Scientific Understanding

In the NGSS, Core Ideas refer to the fundamental scientific principles that students should understand within four specific domains: Physical Sciences, Life Sciences, Earth and Space Sciences, and Engineering, Technology, and Applications of Science. These ideas form the foundational knowledge for students, enabling them to explore more complex scientific concepts as they progress through their education. Having a solid understanding of basic scientific principles is essential for making informed decisions in a world where science and technology play significant roles in our daily lives. Building a strong foundation of scientific knowledge also prepares students for more advanced study after high school and opens up new career possibilities.

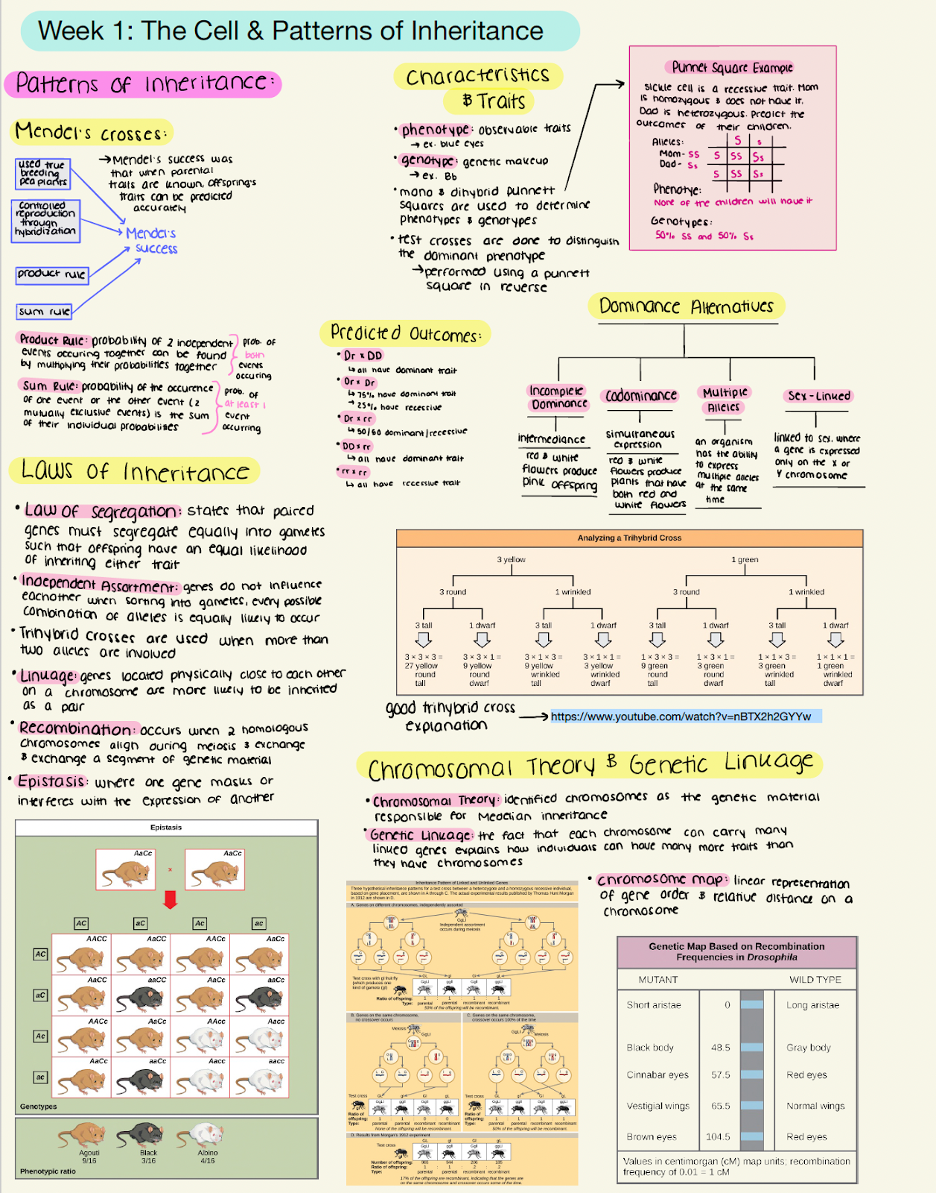

Thinking Maps can be used to help students visualize and understand complex scientific concepts at all grade levels, from PreK all the way to graduate school. They are flexible frameworks for thinking that can be applied to virtually any topic and combined to support more comprehensive exploration and understanding of complex relationships and processes. Using Thinking Maps to take notes, organize ideas and share information helps make scientific information concrete and understandable. That translates to higher levels of comprehension, retention and recall of scientific facts.

Thinking Maps can be used to advance understanding of scientific concepts from PreK to high school…and far beyond. Many students continue to use Thinking Maps as a study and organizational aid well into grad school and in their professional lives.

Want to learn more about Thinking Maps and STEM?

*“Next Generation Science Standards” is a registered trademark of WestEd. Neither WestEd nor the lead states and partners that developed the Next Generation Science Standards were involved in the production of this product, and do not endorse it.

Continue Reading

May 1, 2025

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming education, from custom content in a minute to personalized learning. But with this surge in AI adoption comes a critical challenge for educators and students alike—the need to strengthen critical thinking skills. While AI offers immense potential, it cannot replace the human ability to think analytically, question assumptions, and make independent judgments.

March 19, 2025

When we align instruction with the way the brain prefers to receive information, we can reduce the “cognitive load” of learning and help students maximize understanding, retention and recall. These six brain-based strategies can help educators improve learning outcomes and make learning more fun and efficient.

January 15, 2025

Rather than simply memorizing facts, students with strong critical thinking skills learn how to connect ideas, identify patterns, and make informed decisions—key abilities in a rapidly changing world. These higher-order thinking skills at the core of critical thinking push students beyond rote learning to actively engage with content. In fact, closing the critical thinking gap is one of the most effective ways to accelerate learning for students who are struggling to learn grade-level content.

November 15, 2024

Critical thinking is a cornerstone of success in all aspects of life—not only in academics and on the job, but also in personal decision-making, relationships, and citizenship. And yet, critical thinking skills are rarely explicitly taught. Student-directed activities grounded in real-world problems and applications can help students develop the critical thinking skills they need for everyday life.