We’re Increasing Rigor—But Are We Preparing Our Students?

MARCH 16, 2020

In districts across the country, teachers and instructional leaders are talking about the importance of academic rigor. We expect students to be able to meet rigorous academic standards. We want to see assignments that are academically rigorous and push students to achieve more. We worry that our students will not be prepared to meet the rigorous demands of higher education and the modern workplace.

These concerns have resulted in numerous initiatives to increase rigor in the classroom—many of them introduced with great fanfare and excitement. School leaders invest in teacher training, roll out new programs, and set high standards for lesson planning. Teachers introduce more rigorous assignments that demand more from their students. But too often, these grand plans and initiatives fizzle. Students are not successful with the new assignments, so teachers gradually start scaling them back and stripping out the rigor they just added in. Eventually, we’re right back to where we started.

What’s happening here? Too often, we’re focused on increasing the rigor of assignments—without considering the thinking skills and tools students need to be successful. If we don’t equip our students with the right fundamental tools, all efforts to increase rigor will ultimately fail.

What Do We Mean by Academic Rigor?

Rigor is often defined as the level of intellectual challenge a task requires. The more rigorous the assignment or class is, the more it demands of the student, both in terms of the thinking required and the product delivered. The ideal level of rigor pushes students just a bit beyond their comfort zone; the assignment will feel difficult and require them to stretch their skills but will not feel impossible.

Adding rigor to assignments generally involves asking students to go beyond remembering and regurgitating information and start to apply knowledge and skills. A rigorous assignment asks students to activate higher-order thinking skills and engage with content in more meaningful and challenging ways.

Barbara Blackburn defines three aspects of rigor in her work.

- The task: The challenge level of an assignment should be at the edge of the student’s ability level, but not be so difficult as to cause excessive frustration.

- The skills: Rigorous tasks use multiple skills and ask students to combine skills in a variety of ways.

- The product: Students should demonstrate their understanding through complex, meaningful tasks that allow teachers to assess their level of understanding accurately.

Why Rigor Fails

Most initiatives focus on the rigor of the assignments without thinking about how students will develop the necessary skills. Often, we are asking students to make a sudden leap in the rigor of the tasks they are asked to complete without teaching them the fundamental thinking skills they need to be successful.

Every standard has two components: the content, and what we are asking students to do with it. To be successful, students must be able to manage both. For example, if we want students to explain the causes and effects of World War I, it’s not enough for them to understand the words they are reading. They must also understand what we are asking them to do with the information—in this case, analyze content to extract the root causes and long-term impacts of the conflict. A student who does not understand the task or have the right cognitive skills is likely to turn in a surface-level summary of the information instead of really thinking through the interrelationships of events.

When students don’t have the right tools and skills, the cognitive load of the assignment will be too high. Students spend so much brain power trying to understand what the task is asking them to do they do not have enough left to engage meaningfully with the content.

In this case, academic rigor initiatives can actually backfire. Instead of making progress, students may go backward when assignments are too far above their skill levels. When a student feels like it is impossible to be successful with an assignment, they are likely to shut down entirely. They may not complete it at all or simply put minimal effort into putting something on the page so they can say they have “completed” the work. Not only are they not meeting the intention of the rigorous assignment, they are likely getting even less out of it—in terms of comprehension, content knowledge, and skill development—than they would have from a less rigorous assignment.

Giving students assignments without ensuring that they have the skills to complete them also breaks down student confidence and damages the student-teacher relationship. This often leads to long-lasting negative effects throughout the student’s academic career.

When teachers see students struggle, their first tendency is usually to water down the assignment to a level where students can be successful. Teachers instinctively understand that watching students struggle fruitlessly with a too-hard assignment is of no value to anyone, and all teachers want to see students succeed. Unfortunately, this usually means stripping the rigor rather than providing scaffolding and tools to help students rise to the level of the assignments. For example, they may decide that a surface-level summary will suffice after all and stop requiring students to do the hard work of deeper analysis. This is because most teachers have not been taught how to help students develop the fundamental thinking skills they need to thrive in a more rigorous academic environment.

Preparing Students for Increased Rigor

If we want students to be successful with more rigorous academic standards, we need to equip them with the fundamental skills and tools they need. Fortunately, these skills can be taught and developed.

The cognitive skills that students need to tackle rigorous assignments are the same across all content areas. They are not specific academic skills, but fundamental thinking skills that are linked to the way the brain processes all kinds of information. These are the skills students need to understand both the content that is presented and the task they are asked to complete. Students cannot be successful with rigorous academic tasks without first developing these core cognitive skills.

Thinking Maps are tied to the eight fundamental cognitive skills that underlie learning at every level, from infancy to adulthood: defining, describing, comparing/contrasting, classifying, sequencing, cause and effect, part/whole relationships, and analogies. Higher-order thinking involves activating and combining these cognitive processes in a variety of ways. The ways students use these skills will become increasingly sophisticated as students grow and develop intellectually.

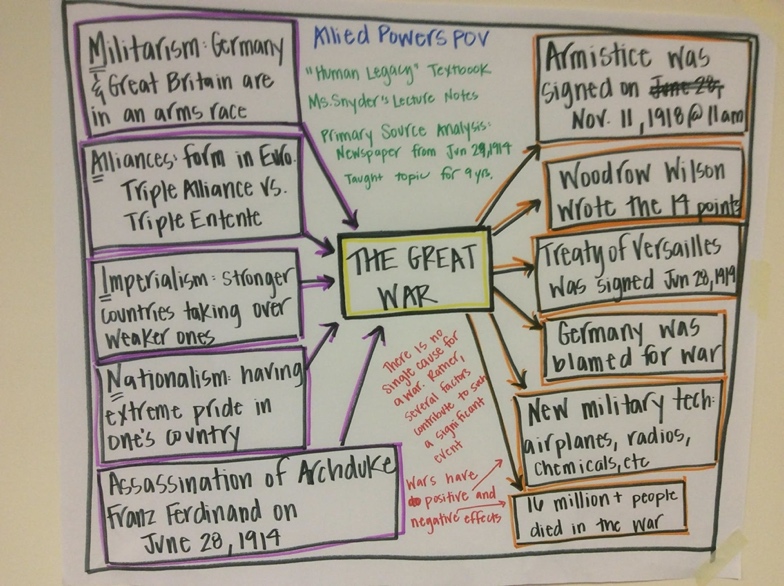

The visual Maps help students activate these cognitive skills deliberately to meet the demands of the task. Students learn the academic language that indicates different kinds of thinking and match the Map they are using to the requirements of the task. In the example above, a student would use a Multi-Flow Map to analyze the causes and effects of World War I.

In this way, the Maps act as a scaffold to help students be successful with assignments that demand rigorous thinking. The Map provides a visual framework that students can use to break down the demands of the task into a format that makes thinking clear and easy. This reduces the cognitive load on the student so they can get down to the critical work of engaging with the content.

Crucially, the Maps are not simply an assignment given by the teacher, but a tool used and owned by the student. As students become proficient in the Maps and the cognitive skills they are connected to, they learn to leverage them to analyze content and improve comprehension, understand the thinking required for different kinds of tasks, and demonstrate their understanding in sophisticated ways.

Thinking Maps is a foundational strategy that multiplies the impact of other initiatives designed to increase rigor. The Maps can be easily adapted for different student needs, helping students of all backgrounds and ability levels rise to meet the demands of academically rigorous assignments. Instead of watering down assignments, we can show students how to use the Maps to activate the thinking required, even if we need to adapt the final product for the student’s language abilities or other learning needs.

Ultimately, academic rigor is not about the assignments we create. It’s about empowering students and giving them the tools they need to activate, develop, and demonstrate rigorous thinking. When we provide them with the right tools, scaffolds, and strategies, all students can be successful in an academically rigorous environment.

Continue Reading

March 15, 2024

Authentic assessment shifts the focus to application of knowledge and skills in the kinds of complex tasks students will face in the real world. Thinking Maps are valuable tools for assessment of student learning, either as stand-alone tasks or as a foundation for authentic learning activities.

February 15, 2024

A majority of teachers believe that students are finally catching up from pandemic learning losses. But those gains are far from evenly distributed—and too many students were already behind before the pandemic. To close these achievement gaps, schools and districts need to focus on the underlying issue: the critical thinking gap.

January 16, 2024

Student engagement is a critical factor in the learning process and has a significant impact on educational outcomes. Thinking Maps enhance engagement by encouraging active participation in the learning process, facilitating collaboration, and providing students with structure and support for academic success.

October 16, 2023

Drawing complex concepts results in better learning outcomes than listening, reading or taking written notes. Learn what the research says and how Thinking Maps can help students tap into the benefits of drawing.