Thinking Maps vs. Graphic Organizers: What's the Difference?

JUNE 15, 2023

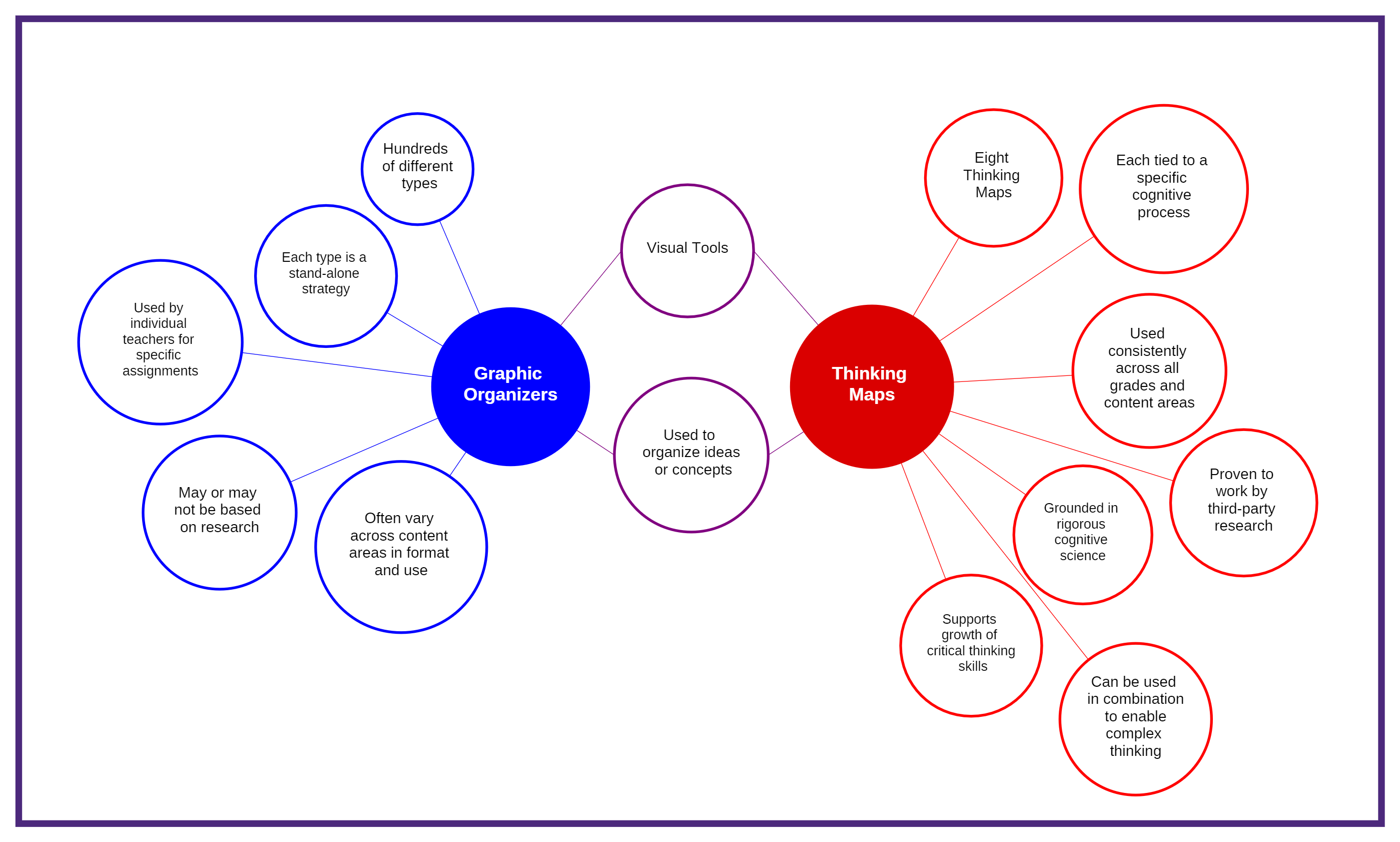

It’s a question we get asked a lot: are Thinking Maps just another type of graphic organizer? If not, what’s the difference? While many people put Thinking Maps in the category of graphic organizers, there are important distinctions in terms of their purpose, use and impact.

Are Thinking Maps a Type of Graphic Organizer?

Yes…and no. Both Thinking Maps and graphic organizers present information visually (i.e., graphically). But that is where the similarity ends. While there are dozens of types of graphic organizers for different tasks and purposes, there are just eight Thinking Maps that are used across all content areas, creating a shared visual language for learning. They offer a structured way to process information that is informed by cognitive science. And rather than simply help students complete a task, they are designed to develop critical thinking skills and activate specific cognitive processes. Here are some of the key differences between Thinking Maps and graphic organizers.

Task-Based vs. Thinking-Based

Graphic organizers such as Venn diagrams, T-charts and flowcharts have been used for centuries to help people organize information visually. Most of these have developed organically over time, and publishers love to create new variations. These graphic organizers tend to be highly task-based; some may be specifically designed for a single assignment or purpose.

In contrast, Thinking Maps are rooted in cognitive science and are focused on thinking. Each of the eight Thinking Maps is correlated to a specific cognitive skill. Together, these eight skills underlie all learning. Thinking Maps work the way the brain works to help students retain and recall information, understand and engage with complex ideas, and organize their own thinking. And they have been proven to work by third-party research. Schools who use Thinking Maps consistently are two times more likely to outperform district peers in reading and 2.7 times more likely to outperform district peers in math.

Variation vs. Consistency

KWL charts. Claim-data-warrant. Learning maps. T-charts. Timelines. Hamburger charts. Students may use dozens of different types of graphic organizers over their academic career, some only in a single class or subject. Each time they are faced with a new type of graphic organizer, they must first figure out what is being asked and how they should use it to organize information. This adds to the cognitive load of the assignment.

Thinking Maps are used across all grades and content areas—and that consistency is important. Thinking Maps aren’t just one-off strategies used by a single teacher. They are a shared visual language for learning across the entire school. This builds automaticity for students in using Thinking Maps and, by extension, activating the cognitive processes to which they are aligned. It also saves time for teachers and makes learning more efficient; instead of spending cognitive energy figuring out how to apply a specific graphic organizer, students can immediately start engaging with the actual content. In this way, Thinking Maps become portable, student-owned strategies that students can use independently through their formal academic life and beyond.

Teacher-Directed vs. Student-Directed

Many graphic organizers are available as downloadable worksheets or provided by publishers to go along with a specific piece of content. This may be convenient, but pre-made blank graphic organizers don’t do much to develop critical thinking skills. Instead of learning how to activate the right cognitive process for the task, students learn to simply fill in the boxes.

Thinking Maps, whether analog or digital, are always created from scratch by the student. Instead of being told what type of visual to use or what boxes to fill in, students learn to analyze the task to determine what kind of thinking is required and, therefore, what kind of Thinking Map they should create. For example, signal words such as “compare” indicate that a Double Bubble Map should be used, while words like “explain the impact” would require the use of a Multi-Flow Map. Details such as the number of bubbles, branches or boxes to use are up to the student to determine. This requires students to think critically to analyze the requirements of the task as they create their Thinking Map.

Stand-Alone vs. Integrated

Each type of graphic organizer is generally designed as a stand-alone task. You wouldn’t typically tell students to use both a Venn diagram and a T-chart together, for example. Each of these graphic organizers is used for a specific purpose.

Thinking Maps, however, are even more powerful when they are used in combination. As students build proficiency with the Maps, they learn how to use them together to engage with complex ideas in sophisticated ways. For example, a multi-Map assignment might start with a Circle Map to brainstorm ideas or build background knowledge, move to a series of Multi-Flow Maps to predict the effects of various proposed courses of action, and finally to a Flow Map to plan the steps in a process. Students learn to use the eight Thinking Maps alone and in combination to build cognitive flexibility, complete complex multi-part tasks, and support deep comprehension.

Building Critical Thinking Skills with Thinking Maps

When deciding between graphic organizers and Thinking Maps, consider the ultimate goal: is it simply to have students complete a task, or is it to equip them with a versatile toolkit for higher-order thinking? While traditional graphic organizers can be used to organize information and visualize relationships, Thinking Maps elevate this process by grounding each Map in a specific cognitive skill. This approach aligns more closely with the ultimate aim of education: fostering not just rote learning but the development of critical thinking skills.

Ready to build critical thinking skills at your school? Talk to a Thinking Maps representative to get started.

Continue Reading

July 2, 2025

A Meta-Analysis of studies showed that coaching, along with group training, curricular and instructional resources made a larger impact on the effects of teaching and student achievement.

June 16, 2025

At Thinking Maps, we are committed to creating a platform that not only meets but exceeds the expectations of our users. That’s why we’re thrilled to roll out a host of new user experience updates to the Thinking Maps Learning Community (TMLC). These updates represent a significant leap forward in usability, design, and functionality, ensuring a seamless and engaging experience for all users.

May 29, 2025

When it comes to professional learning for teachers, coaching has emerged as an effective method for fostering meaningful, long-term change in teaching practices. By offering personalized support, ongoing feedback, and practical application, coaching meets teachers where they are and provides the tools they need to thrive.

May 1, 2025

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming education, from custom content in a minute to personalized learning. But with this surge in AI adoption comes a critical challenge for educators and students alike—the need to strengthen critical thinking skills. While AI offers immense potential, it cannot replace the human ability to think analytically, question assumptions, and make independent judgments.